Arthur Rimbaud: The Golden Dawn

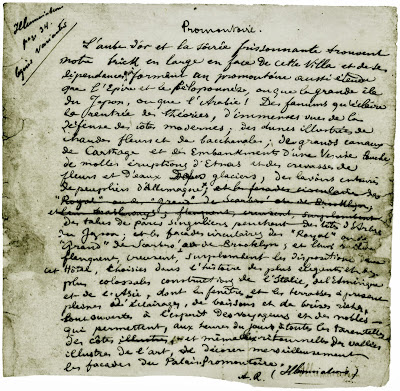

The lost manuscript of Rimbaud’s Promontoire. Note that someone – but not the poet – has added the word Illuminations in the lower right corner of the manuscript. Under this is another word, this time written in Rimbaud’s hand.

Promontory

The golden dawn and the sensational evening find our brigantine anchored out in the roads opposite this villa and its outbuildings, which form a promontory as extensive as Epirus and the Peloponnese, or the vast island of Japan, or Arabia! Temples illuminated by the return of theories, immense views of modern coastal defenses; dunes illustrated with warm flowers and bacchanalia; great canals of Carthage and embankments of a degenerate Venice; mild eruptions of Etnas and crevasses of flowers and glacial waters; wash houses near stands of German poplars; mounds in odd parks where the head of a Japanese tree bows down; and circular facades of Royals or Grands of Scarborough or Brooklyn; and the railways flank, undermine and dominate the outlay of this Hotel, chosen from the history of the most ornate and colossal constructions of Italy, America and Asia, whose windows and terraces now full of lights, drinks and rich breezes, are wide open to the souls of travellers and nobles – who allow, during daylight hours, all the tarantellas of the coast – and even the ritournellas of the illustrious valley of art – to decorate in a miraculous way the facades of the Promontory Palace.

A wonder-of-the-world: St Pancras Railway Hotel as Rimbaud would have known it in 1873. Here we are looking west, but from Great College Street the view of the newly-opened terminus would have been from the north. Rimbaud would have sighted down the great trainshed, which we see here in profile, stretching out to the right. (From Pentonville Road looking west: evening (1884) by John O’Connor.)

The Roofscape

The unthinkable happened in two phases.

I’d seen the main landmark from the roof of the derelict. Gazing south across the housetops towards Bloomsbury I’d looked up – from Rimbaud’s Promontoire – and visually traced the Gothic silhouette of Gilbert Scott’s St Pancras Railway Hotel. This seemed to mirror ‘in a miraculous way’ Promontoire‘s coastal palace of military aspect. I observed – at dawn and at nightfall – this Red Fort somehow transported from India to London, this Castle Gormenghast in the distance with it’s many substructures and ‘dependencies’. I saw the justness of comparing it to a headland ‘as large as Arabia’. I saw the rightness of conceiving it as nothing less than ‘the vast island of Japan’. But had Arthur Rimbaud ever set foot in Kings Cross?

A line in Wallace Fowlie’s introduction spoke of intermittent trips to Brussels and London. That was all I knew.

I dismissed the Promontoire identification. Surely the whole point was that Rimbaud’s prose-poem was non-specific, all-inclusive, encyclopaedic? Yet, amid all the plurals of ‘Temples’, ‘dunes’, ‘canals’, ‘Etnas’, ‘laundries’, ‘odd parks’, ‘Royals’, ‘Grands’ etc, I noted that Rimbaud introduced his main landmark as ‘this villa’: singular. And another point struck me. Promontoire might be an exercise in spatio-temporal synthesis, an experiment in topological compression, but the ‘villa’ was described as ‘flanked, undermined and dominated by railways’. In other words, though the coastal structure seemed classical, ancient – biblical and pagan – it was clearly situated in the modern world. Or, if Rimbaud’s superstructure was outside time and space, its architectonics referenced antiquity and modernity.

The ‘castle as the universe’ is a constant motif in fairytales and folk-mythology, looming large also in Arthurian literature. A complex of roofscapes, towers and spires captures our experience of a multiple-faceted reality.

The Second Wave

In Promontoire Rimbaud tells us that he ‘finds’ himself observing ‘this villa and its dependencies’ from his brigantine ‘out in the roads, opposite’ the shoreline. (The phrase ‘out in the roads’ is a maritime expression meaning ‘lying offshore’ and I use it – playfully – in my translation feeling that if Rimbaud had found such a double-meaning in French the term might have appeared in his extraordinary poem, a poem which – as I hope to show in a moment – should rightly be considered the mother of all the Illuminations.)

In the days and nights following the rooftop vision of the promontory-palace as St Pancras Railway Hotel, I started reading about the poet’s life from Enid Starkie’s pioneering biography, acquired almost immediately after the revelation. Then, in the second phase of a rite of passage, less than a week after the first epiphany, I located Rimbaud’s brigantine architecturally ‘anchored’ in Royal College Street. His pirate-vessel, his Drunken Boat – ‘notre brick’ – was only a hundred yards from my derelict. (The French poet-laureate studied English assidiously, so the playful crossover from ‘brick’ as in ‘housebrick’ to the French ‘brick’ – for brigantine – would have certainly appealed to someone who constantly resourced maritime images in his work.)

The original identification of 8, Royal College Street as Rimbaud’s brick-and-mortar pirate-ship was triggered by my first (post-midnight) visit to the house when I noticed immediately its strange prow-shaped parapet – west-facing at the front of the house – a feature unique to this Georgian property. Naturally, after a few more fanatical reconnoiterings, I knocked on the door one sunny spring morning. (At this point there was still no plaque on the house.) A gentleman who looked like Rowan Atkinson – vaguely hyperthyroid eyes in a mobile, Machiavellian face – answered the door, looked me up-and-down. To my amazement he seemed to know exactly why I’d come. When I mentioned Rimbaud he said immediately: ‘I smell his pipe at night. It’s extremely pungent!’

The faithful were clearly hammering on his front-door quite frequently.

The initial map of subjective interpretation began to make sense in the light of the second revelation. The pirate-ship of all time reminded me of my own derelict. I strode the deck more proudly under the black flag of the squatocracy, scanning around with my poetic telescope.

There was plenty to see.

We saw ourselves as nonviolent levellers of direct action, we saw ourselves as visionary demographic outlaws setting up new paradigms of urban living. In the shadows of the towerblocks of Somers Town we were living in ‘the miraculous valley of art’.

In subsequent psychogeographical explorations of the quarter, trying to block the monoxide fogs and project myself back into late Victorian times, I noted – ghostly revenant – that, approaching 8, Great College Street from the west presented a view of the ship-like frontage from as far away as the High Street itself, a distance of a good few hundred yards. King Street (as it was before it became Plender) ran in a straight line from Camden High Street all the way to the doorstep of the ‘household in Hell’.

A royal road indeed!

The image of the ‘prowed’ house would have imprinted itself early in Rimbaud’s second ‘London pilgrimage’.

The house of Arthur Rimbaud in Royal College Street (or Great College Street as it was in his day) very much as I first found it in the early spring of 1973. (But at that time there was no plaque in evidence.)

Climbing Gormenghast

Still – at this time – there was no bigger vision.

I didn’t – yet – really suspect that Rimbaud might have found something extraordinary in Kings Cross St Pancras. (Shall we call it ‘the place and the formula’?) I was troubled by the transmutation of this shabby zone into something otherworldly: the shimmering cityscapes of Promontoire.

With the poet’s Collected Works in my hand I climbed every morning through the hatch of a dim, dusty attic and explored a little spillway between the chimney-stacks. Topside, swaying on the west-facing front parapet, or reclining on the silver-grey sloping roof-tiles, or walking up and down speaking Promontoire aloud Rimbaud’s words became increasingly supercharged. Soon I knew the poem by heart in both French and English. As invocation deepened the sorcery intensified. It seemed that – cycling Promontoire as a prayer or a mantra or a magic spell – I could slip through some hairline crack in the everyday world and enter the zone of Anima Mundi: the mindspace of the living universe.

For the first time since losing the guitar to tendonitis, dynamism came back, energy took over, enthusiasm flooded the sensorium: everything changed. Now my single reason for living stared me in the face from the Collected Works. I even dreamed of Rimbaud’s miraculous text. No archeologist excavating a Sumerian palace-library and finding lists of kings from before the Flood was ever more deliriously excited than I was – handling the precious ‘clay tablet’ of Promontoire.

I sensed there were more meanings beneath the sand. There was more information under the Promontory Palace.

Curious ideograms on a Sumerian clay tablet (retrieved from the western deserts of Iraq).

The Order of the Golden Dawn

Once again I went back to the very beginning. (Now I began an inch-perfect analysis of Promontoire.)

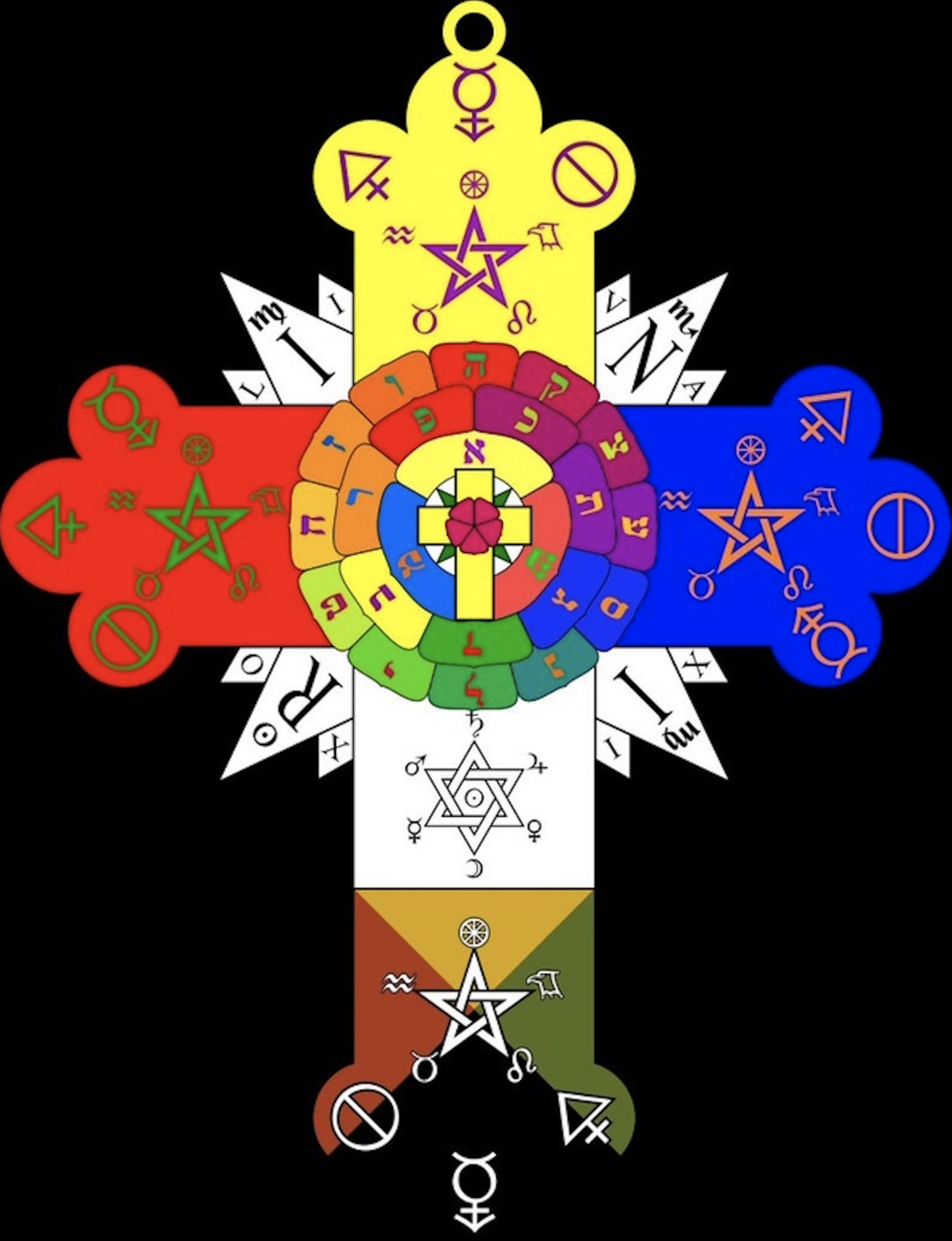

For a long time I’d been aware of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Yeats’ involvement in ceremonial magic had interested me greatly for quite a few years. Now I had learned that the Golden Dawn’s Inner Temple – the oratory of the esoteric Second Order – had once been located in Kings Cross St Pancras, at 62, Oakley Square to be precise. (Oakley Square is roughly equidistant from Pancras Church and 8, Royal College Street.) Unlike the Isis-Urania Temple, founded in 1888, Oakley Square was the headquarters of the order’s operative adepts and active magicians. The Golden Dawn’s magical workings happened here. (The outer-order Isis-Urania Temple in Hammersmith was only for theoretical and novitiate studies.) Three streets away from Pancras Church certain rites were performed – some lasting many days and nights – rites specifically designed to immanentize – to bring about – the new age called the Aeon of the Child.

Who named the Order of the Golden Dawn? (This question occured to me late one night.) Was there a way to link Rimbaud to the naming?

A bridge was created by a close friend of WB Yeats. This obscure individual was an outer-order Golden Dawn satellite: the minor poet – but fairly important critic – Arthur Symons. It emerged that in the autumn of 1893, on the night of November 19th, Paul Verlaine – at the invitation of Arthur Symons – caught the night-boat to London in order to deliver – on the 21st – what turned out to be the most laidback disquisition ever heard by earnest late-Victorian literateurs. By this time – only three years before his death – Paul Verlaine was a bibulous ruin, moving about deliberately on a stout stick. His lecture amounted to a series of detours through personal reminiscence and belletristic anecdote during which he also mumbled quite a number of his poems. But in spite – or perhaps because – of being three-quarters drunk, he hypnotised his audience that night in ancient oak-panelled 14th century Barnard’s Hall (situated – interestingly – directly above the Fleet River, immediately south of Kings Cross in Fetter Lane).

The important point here is that just before this period Verlaine’s reputation had sunk very low indeed, thanks mostly to his alcoholism. (He hadn’t produced any new work for many, many years.) And yet he had quite recently cleverly resurrected himself by publishing – for the first time – Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations. In Barnard’s Hall he must have spoken about this achievement, an event which set literary Paris ablaze. Necessarily that night he regaled his listeners with some account of the Promethean boy who had turned French literature upside-down, the Mighty Youth who destroyed the Parnassians. (A mythological subject!) With all the lyrical murmuring and mumbling that went on it is just possible that, in the course of his ‘lecture’, Verlaine recited something by the legendary Rimbaud. Something from the London-inspired Illuminations possibly?

Was W.B Yeats in the audience that night?

It is hard to imagine his absence. If he wasn’t in attendance, he certainly heard all the news from Symons. So the term ‘the golden dawn’ could very possibly have filtered across to the magical order from Rimbaud’s Promontoire.

The Lord of Two Horizons

I have mentioned that according to the Western Magical Tradition (to which Rimbaud and Yeats – as most-important English-language poet of the last hundred years – both belong) there is an association between Kings Cross St Pancras and the formula of a golden sunrise, a sacred aurora, a daybreak of spiritual light. I have also referenced (in Arthur Rimbaud: The Brigantine) the fact that the iconography and symbolism of the child-martyr Pancras allow us to compare him/her with other child-pantocrators such as the Chinese Pan Ku, the Celtic Mabyn and the Egyptian Horus.

In his iconography Horus is represented with one finger sealing his lips. (I find it interesting to reflect that apart from his poetry Rimbaud is most famed for his silence.) And Horus – who in Golden Dawn symbolism presides over the Aeon of the Child – is also called the Lord of Two Horizons. (In fact the very word ‘horizon’ has come to us – via the Greek ‘horos’ for landmark or boundary-stone – from the ancient Egyptian god-name.)

The two ‘horizons’ of Horus are dawn and dusk. When the adolescent god is titled ‘Lord of Two Horizons’, Egyptian cosmologers are believed to be referring to the rising and setting sun in one divine ‘person’. And the hermetic implications of Promontoire’s opening phrase accord even more profoundly with the symbolisms of Egypt because the solar child-deity Horus rides the two horizons in a sunship. Clearly there is a direct equivalence between Rimbaud’s brigantine and the solar barque of Horus, the child-deity who becomes Pancras in Christian cosmology, the patron saint of teenagers and truth. And the sacred watercraft of Horus could be described as a pirate-ship because Horus is outcast, an adolescent warrior for truth, the avenger of his absent father, Osiris. (Set – or Satan – is the uncle of Horus and murderer of Osiris, so Hamlet too can be seen as a sort of Horus-figure, isolated from the establishment, driven to extreme actions.) In one pungent myth the young god Horus is homosexually raped by his power-mad uncle.

An ‘outcast warrior for truth’ sums up Rimbaud. He asks our entire civilization to turn back, to think again and live from the heart. He proposes that consciousness is a transmission from the Other (‘I is another’) and he promises that if we can transcend self-image we will reinvent love and experience ‘Christmas on Earth’. Yet his dream of transforming the world begins with transforming himself into the alchemical ‘sunchild’. This means achieving an inner balance which is beyond male/female duality, an individual androgyny which builds on the strengths of both sexes, which overcomes the war between matriarchy and patriarchy.

‘What was I saying about a friendly hand! One fine advantage is that I can laugh at old lying loves, and strike with shame those lying couples – I saw the hell of women down there – and I shall be free to possess truth in one body and one soul.’

The philosophical cross of the Order of the Golden Dawn

The Mother of all Illuminations

I imagine Rimbaud, that most cosmological of poets – who hides scholasticism and learning under incredible lyricism and casual vernacular – walking back to Great College Street from the British Museum where he has just spent a blissful afternoon in the reading-room immersed in Ethiopian genealogies and Egyptian creation-myths.

He is interested in the unbroken line from King Solomon down to the Emperor Theodore, the bloodlines of the Solomonic dynasty. Studying African Christianity he’s tracing mythological connections between ancient Ethiopia and pharaonic Egypt. Fascinating obsession, fixation. (The figure in the modern world who most resembles Rimbaud is Bob Marley. In a later article I’ll discuss the light of Rastafari; and probe why Arthur Rimbaud is a significant inflence in hiphop.)

As he walks, in his mind is the first line of a new poem. It remembers a recent crossing on the Ostend ferry yet it reaches up into skies of cosmology. It glides on a sea-crossing to the white cliffs yet it’s down-to-earth and grounded in the strange zone of Pancras. (Where he finds himself at present, lucky circumstance.)

It goes something like this:

The golden dawn and the magical dusk find our sunship out at sea…

I want very much to continue as soon as possible with the process of putting Promontoire under a critical microscope, looking at this key text with high-magnification. There is much more material to consider. But for now I will close this present essay with the details of a discovery – not mine – which need to be disseminated among true Rimbaudians everywhere. In the 1961 Faber edition of her seminal biography, Enid Starkie includes a new passage which does not appear in the book as it is issued in 1938 (by Hamish Hamilton). Here is the quote in its entirety:

‘It is not known if the title Illuminations, which seems to bear the hallmark of Rimbaud’s genius, was certainly his – though this is highly probable. The word is written on one of the poems, Promontoire, but not in his handwriting, and it is not known who put it there. However, underneath that word, which is in the plural, can be faintly seen, in certain photographs, but not in all, the word Illumination in the singular, in another hand, and I agree with De Graaf in thinking that it is very similar to Rimbaud’s. The manuscript of the poem has disappeared.’

Postscript.

An astute reader has written within a few hours of my posting ‘AR: The Golden Dawn’ pointing out a minor inconsistency in my argument. I am not a historian of the Order of the Golden Dawn; but still I feel I should have noticed this simple error; and I thank my correspondent for drawing my attention to the flaw in my line of reasoning. Verlaine’s London talk on the 21st November 1893 happened five years after the founding of the Golden Dawn, so he could not have been the carrier of the name. It seems that the Ordo Hermeticus Aurorae Aureae styled itself the Golden Dawn from day one in 1888. (As I say, I’m not a historian of the order and this is where my confusion lay, I could find no exact details about the very beginnings of the operation. A long time ago I studied the Golden Dawn and its precepts quite closely but these days my mental filing-cabinets on the subject are all cleared out and emptied away.) Having said all this and de-bugged the essay – I trust – I would still draw attention to the fact that Verlaine’s edition of Illuminations appeared in 1886, two years before the birth of the GD. So Rimbaud might still be the source of the name, though admittedly it could also have come through various neo-Platonic philosophers and their schools.

The house of Arthur Rimbaud today, showing the ‘prow’ of the ‘brick‘, the brigantine. (I am not aware of any other Georgian house in London having a similar pyramidical feature.) A brigantine was a small two-masted vessel often associated with piracy. It is believed that Rimbaud and Verlaine occupied the top floor at number eight.

The room in Barnard’s Inn, Fetter Lane, where Paul Verlaine delivered his poetic lecture in 1893. Fetter Lane in Holborn lies directly above the underground River Fleet, London’s most important lost river. The Fleet also runs beneath Royal College Street.

Recent Comments