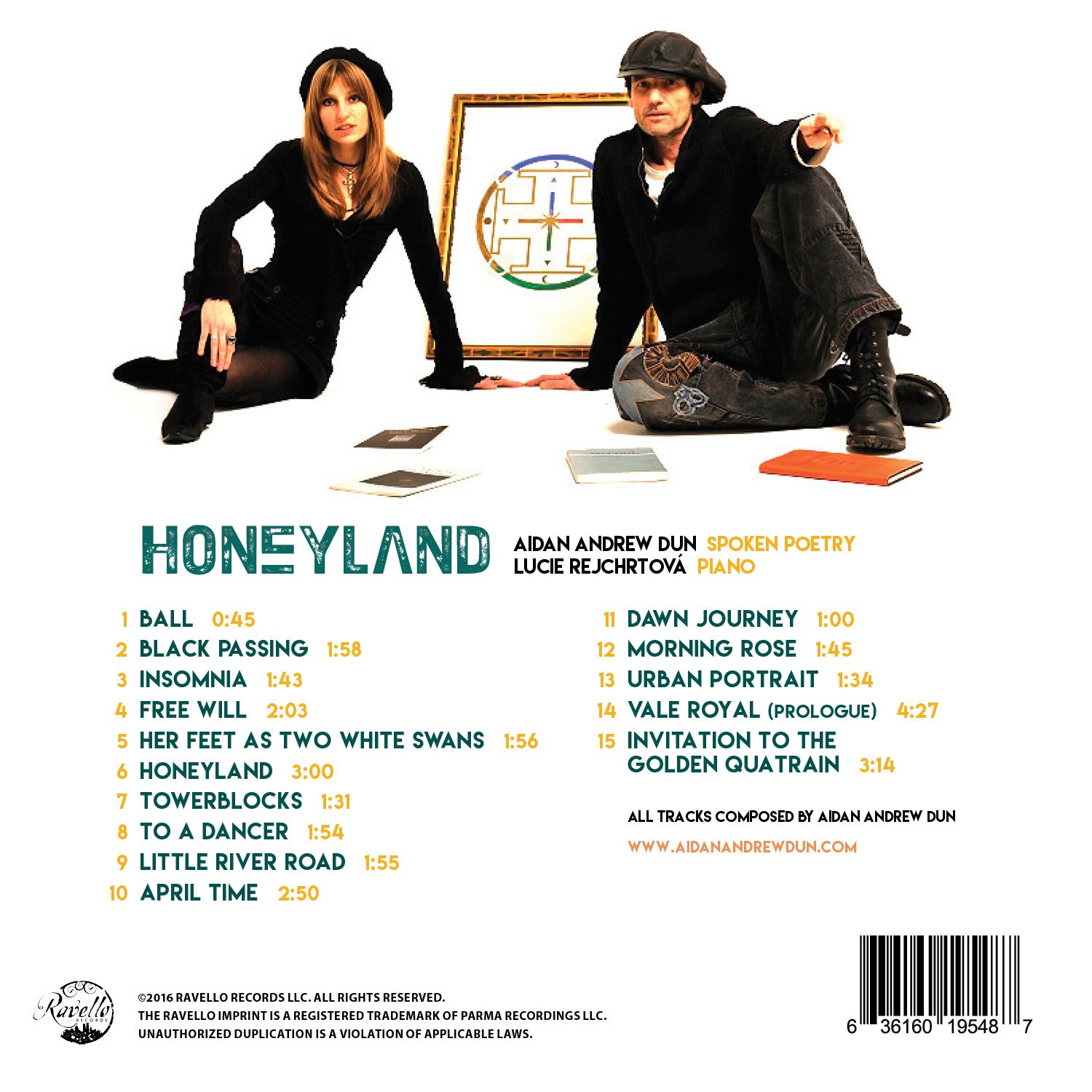

RAVELLO RECORDS INTERVIEW WITH AIDAN DUN AND LUCIE REJCHRTOVA ABOUT THEIR ALBUM HONEYLAND

How was “Honeyland” conceived, and what were some of the main influences behind the works?

AAD:

Around 2006 I sketched twelve or fourteen piano pieces in the studio with the idea of using them as settings for poems and I experimentally uploaded a few of these ‘wordscapes’ to my website. Then, rendezvousing with Lucie Rejchrtova in Amsterdam (where I was reading) in a crowded room she mysteriously beckoned me over to an old out-of-tune upright piano and out-of-the-blue played a few of my piano compositions. I almost fell to my knees with surprise; it appeared she had learned these pieces from my website. I was astonished because I’d long resigned myself to the fact that I could not possibly deliver the poem’s settings while reciting since my piano technique is far from perfect. So Lucie and I began working together towards preparing the Honeyland material for performance (and the studio) the magical sensitivity of her playing making it possible to launch this work properly at last.

I’ve always instinctively rejected the notion that poems belong in books, flattened onto two-dimensional pages. (It must be the reincarnated troubadour in me that feels an intense bereavement around the disconnect between poetry and music.) But if poems don’t belong in books where are they ‘at home’? To put the question another way: through which medium can a poem best be transmitted? Eliot points out somewhere in an essay that only a fraction of meaning from the recitation or reading of a modern text normally sinks in on first encounter; and many indeed at initial contact become bewildered quickly and give up on poetry and its incomprehensibility, alienated. With Homer (whose poets deftly handle the lyre before their stanzas are declaimed) I maintain that music sympathetic to the atmosphere and spirit of a poem – preferably composed by the poet – can induce a hypnogogic state in the listener which opens the way to its intentional language.

I partly view music as an abstract ‘page’ on which poetry can be written. No typographical or visual medium enjoys music’s special relationship with the spoken word. It surely cannot be argued that a similar natural symbiotic partnership between poetry and the visual arts exists. For instance, the whimsical experiments of concrete poetry have never to my mind produced a convincing frisson. Games played with the arrangement of words on the page in my view fail utterly to lift poetry into another dimension and, on the contrary, seem to contribute to the literal disintegration of language. Concrete poetry strikes me as a fruitless attempt to reinvent textuality, producing an effect far from the powerful combination of a poem well-mounted on a sympathetic harmonic platform.

Through, I suppose, a kind of synesthesia I have always sensed words as traces of melody. I have always imagined my poems afloat on sound; and Honeyland is the realization of that old, almost atavistic, dream. In composing the pieces on this album I’ve striven to express poetic lines as melodic statements, to render both rhymes and alliterations as the extensions of chords. I want listeners to be convinced that the crafted inflections of a poem have much in common with the contours of musical cadence.

For a long time, through my twenties and thirties, my struggle to write poetry precluded serious composition. In my forties, with a body of published work, I began exploring the piano with specific poems in mind (as I mentioned before). By that point in my life I had to some extent come to terms with the loss of the classical guitar, having been forced to say farewell to that instrument due to practice-induced tendonitis.

Influences have been many and various. My grandmother, Marie Rambert, dancer and founder of the Ballet Rambert, joined the Ballet Russes just at that point when the Ballet Russes was rehearsing with terrible difficulty The Rite of Spring. Rambert was able, through her special training with Jaques Dalcroze in Switzerland, to form an interdisciplinary bridge between Stravinsky and Nijinsky: she became the essential nexus which saved the work from imploding. (The rhythms of the score were incomprehensible to the dancers.) Engaged by Diaghilev to act as an intermediary between Stravinsky and Nijinsky Rambert went on to dance in the famously apocalyptic premiere of Sacre in Paris before fleeing to London just before World War One.

Mim (as everyone called her) introduced me to Stravinsky’s ouevre and in my late teens I devoured everything he had written. His Symphonies for Wind Instruments hypnotised me like Bach’s Passacaglia in C Minor; while Bartok’s largescale work, Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, actually precipitated an out-of-body experience which haunts me to this day. These composers mingled their influence with that of Debussy, Ravel and Prokofiev whose canon was familiar to me from earliest recollection because my father was a skilled and emotive pianist. His interpretations of Gaspard de la Nuit, Passepied and L’Isle Joyeuse had lulled me to sleep on many a hot tropical evening in the West Indies where I was raised (though I was born in London).

Jazz became very important to me in my twenties, Coltrane and Andrew Hill and in particular. The West-African (Malian) singer-guitarist Ali Farka Toure has also been an inspiration.

You’ve said something about your musical background, could you now say something about the work itself, this fusion of poetry and piano music.

AAD:

Honeyland is dedicated to Cedella Booker (1926-2008) the mother of Bob Marley, regarded during her life as Jamaica’s First Lady. Describing (in her wonderful biography of her son) her struggle to raise Bob all on her own in the hills of Nine Mile ‘Ma’ Booker mentions a green mountain-retreat where she found solace and comfort when times were harsh: the place she called ‘Honeyland’.

There are fifteen ‘wordscapes’ here, my own compositions performed by Lucie Rejchrtova combining a relaxed modern delivery with a classical impressionistic feel.

Is this a new approach entirely? I am not aware that my contemporaries have used a similar modality. Greek poets of the Homeric era incanted lyre-in-hand (the recitative of opera was supposed to be a reinvention of the Greek art of incantation, in which the harpsichord replaced the lyre) so perhaps Honeyland is an attempt to revisit the performance-poetry of antiquity. Yet I cannot help feeling that the future of poetry lies in this art-form forging an ever-closer symbiotic relationship with music. I often ponder the post-literary Rimbaud returning to his mother’s farm in the Ardennes from one of his wanderlust adventures and carving a piano-keyboard on the dining-room table while Shadowmouth – Madame Rimbaud’s nickname with her son – was downtown on a shopping expedition. (A few days before she had pointblank refused to buy him a piano when he announced to her that he had invented a new kind of music.) Madame Rimbaud, a workaday Ardennaise peasant with profoundest religious convictions, returned to find the prophet silently practicing his new music at the defaced table.

In performance I deliver these poems from memory. I feel that for a poet a book in the hand is a screen which can form a barrier with (and for) an audience. Memorization is not that difficult for me because by the time I’ve ‘finished’ writing a poem it is three-quarters memorized.

Poetry-on-the-page I regard almost as an anachronism. Sometimes – on bad days – I consider books to be prisons in which poets are incarcerated, held like dead flowers between stifling colourless pages. The age of typography may be passing; and, if so, this is interesting because written language implies slavery, since where the written code exists elites with exclusive keys to codified knowledge will guard against education and emancipation. A return to the shamanic incantation of the spoken word may imply a liberation not only aesthetic but demographic and societal.

What I’ve striven for with the Honeyland collection is a streamlined minimal delivery superimposed on simple piano studies. (The most complex pianistic passage in the sequence – the electrifying introduction to Free Will – is in fact an improvisation by Lucie Rejchrtova on my very straightforward chord-cycle.) And I hope the more abstract engine of music will power listeners to my humble poems to a world where the word is still unfallen, where language and sonority are one.

LR:

I perceive Honeyland as a multidimensional painting or a map where each song is a different borough; or a sea-realm of sound and melody where words are ships that can transport the listener to different latitudes of imagination.

When we perform Honeyland live, a visually-rich world opens in my mind. I hear lines of the poems in colour, a synesthesic experience. I often quietly hum simple melodies over the patterns I play, and these hummings seem to me almost mantric, part of the ritual of the presentation of the work.

What will this release mean to you?

LR:

People have different ways of perceiving the poems during our live set, focusing either on the lyrics or the melodies. Having the actual album will mean they can listen to a piece of their choice as many times they want, and concentrate on any of the aspects that interest or move them in particular.

I love performing Honeyland live and the chemistry is always different with changing audiences and situations. At the same time I love listening to Honeyland on top of a double-decker, appreciating the noble shabbiness of London even more. So it feels good to know that others will be able to take the poems with them anywhere they like, and hopefully Honeyland will help them to transform the ‘coming back from work’ experience into a unique journey of the soul, when imagination awakes and paints whole new universes in front of the mind’s eye.

What goals do you have for “Honeyland” and the rest of your works?

AAD:

One alluring idea is to find a studio (here in London perhaps, or elsewhere) in which to simultaneously record and film a recital of Honeyland. I also like Lucie’s idea of a ballet: the anchoring of dancers in the physical body could act as an interesting counterpoint to more abstracted channelings. I imagine the dancers listening to the words, then dancing-out their drift while the speaker watches them.

Another attractive prospect is the idea of performing the collection Stateside. The Beat movement in American poetry with its confidence, outspokenness and sacred irreverence, has influenced poets in all cultures worldwide but can the island of the mother-tongue claim such a literary impact in the last fifty years? In spite of the best efforts of Dylan Thomas and Ted Hughes it is doubtful.

I sometimes feel that British poets are hypersensitive to the paradoxical situation of the English language in the context of Europe. On this tiny island we speak the world auxiliary-language but find ourselves adrift in a local sea of languages that appear to be gradually dying, though of course this is not true of Spanish. Sadly, French, the most musical of the Romance languages, is in decline and for French poets this is of course a devastating issue. The British poet does not have quite the same problem. He feels the proximity of threatened – and sometimes understandably paranoid – guardians of dying tongues and his response is to become even more muted and conservative, cultivating an almost apologetic Anglophone caution and politeness which undoubtedly represent a kind of curse.

We’d love to perform in America where, I feel, poets are more out-of-tune with the modern world, more in touch with Anima Mundi and zeitgeist. Yeats is the last poet of the British Isles (as they used to be called). The ‘deep songs’ of the twentieth century are all American, as they were French in the nineteenth. Talking about performance, I’m not really a hundred-percent behind the term ‘performance-poet’: poets are not actors ‘performing’ their poems. In the act of delivering their work they are supposed to remove masks rather than assume the personae of stagecraft. When the poet is publicly possessed by his or her muse, only then will enchantment take place. I become nervous before a recital but on a good night I will consciously pass the juncture at which ego says to overself: “Take over, I’m out.’

I can easily pinpoint the apogee of my career so far: an unforgettable autumn evening in 1995 when Allen Ginsberg flew in from New York to participate in the launch at the Royal Albert Hall of my epic poem Vale Royal, a work which had taken twenty-three years to write, a study of the psychogeography of King’s Cross Central at the heart of London. As a completely unknown poet I recited that night to an audience of more than four-thousand.

Allen later duetted his ‘Ballad of the Skeletons’ with Paul McCartney on guitar:

Said the Buddha Skeleton

Compassion is wealth

Said the Corporate skeleton

It’s bad for your health …

Said the Ecologic skeleton

Keep Skies blue

Said the Multinational skeleton

What’s it worth to you?

I anticipate – dreamily – the auditoriums of America.

LR:

I’d feel Honeyland could be performed on different stages with many settings. It’d be great to see a balletic interpretation. I can also imagine it as a film soundtrack, or hear it interpreted in a really different ways, e.g. as a hip-hop version. In fact we do sometimes perform a funky version of Towerblocks, an atmospheric, minimal, laid-bare hip-hop treatment.

Recent Comments