Arthur Rimbaud: The Third Man

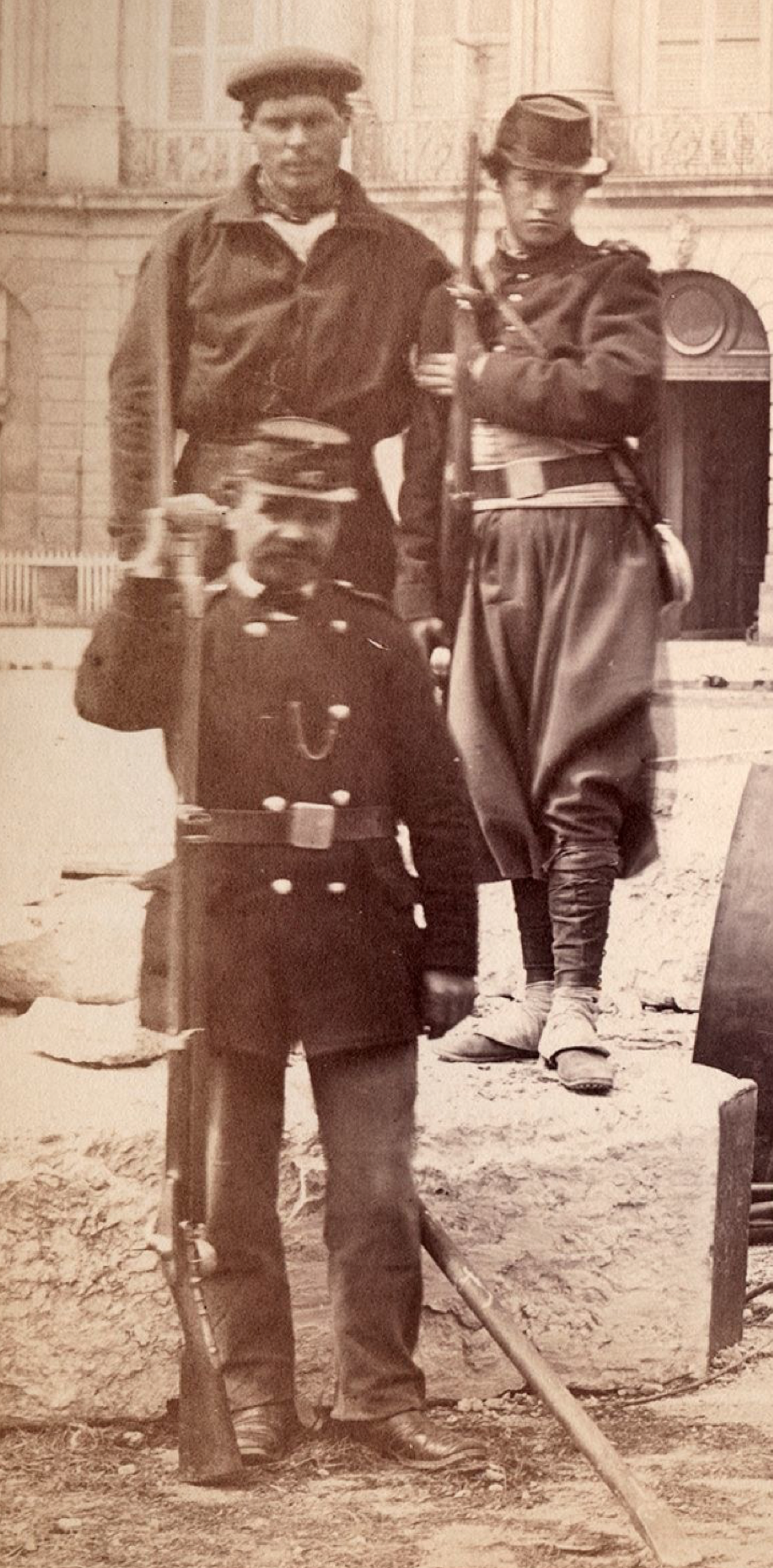

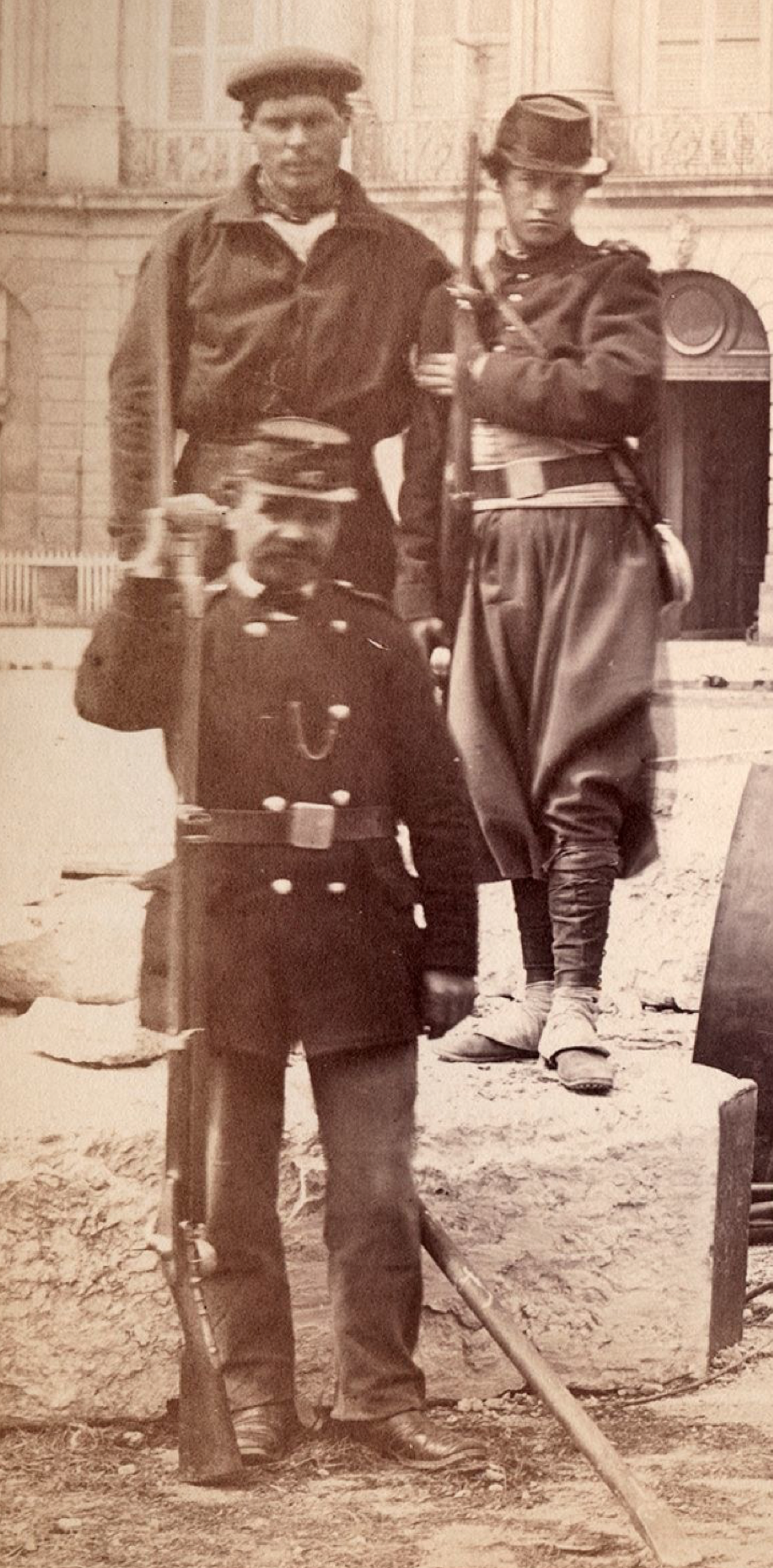

The enigmatic trio of the Place Vendome. The ‘third man’ stands closest to the camera, smiling.

Positive choreography

In Bruno Braquehais’ group-portrait most probably showing Arthur Rimbaud in the Place Vendome the poet is the psychological focus of the plinth-group. An inverted triangle comprises the poet himself, his friend from the 88th regiment (who places his left hand on Rimbaud’s left shoulder in a cordial and protective gesture) and a third man who stands in the foreground almost like a herald. I’d now like to examine the identity of this last figure.

The third man is the nearest person to the camera, which works to his advantage because in this position his height is amplified by his proximity. In fact we don’t realize how small he really is because of this clever photographic positioning. (The placement of this individual contributes to the argument for a completely choreographed ensemble where selected characters are represented in symbolic poses. Note also how the middle-distance group of Communards are distributed in geometric symmetry, strung like beads on the guard-rope which defines the central third of the composition. A triangle touching both ends of this rope will have its apex exactly in the centre of the photograph, while its two lower points neatly bisect the lower corners. This layout of this image has been proportioned for visual harmony.)

The third man thrusts himself importantly into the foreground yet at the same time he seems to make it clear that he doesn’t consider himself worthy of standing on the plinth. His kindly and intelligent face wears a slightly bashful expression. This individual seems to say he’s proud to be near Arthur Rimbaud but we note that he consciously places himself so as to obscure only the giant while leaving the visual path to the poet clear. By his act of stepping-aside our view of Rimbaud is absolutely unimpeded. (One more argument for careful choreography.)

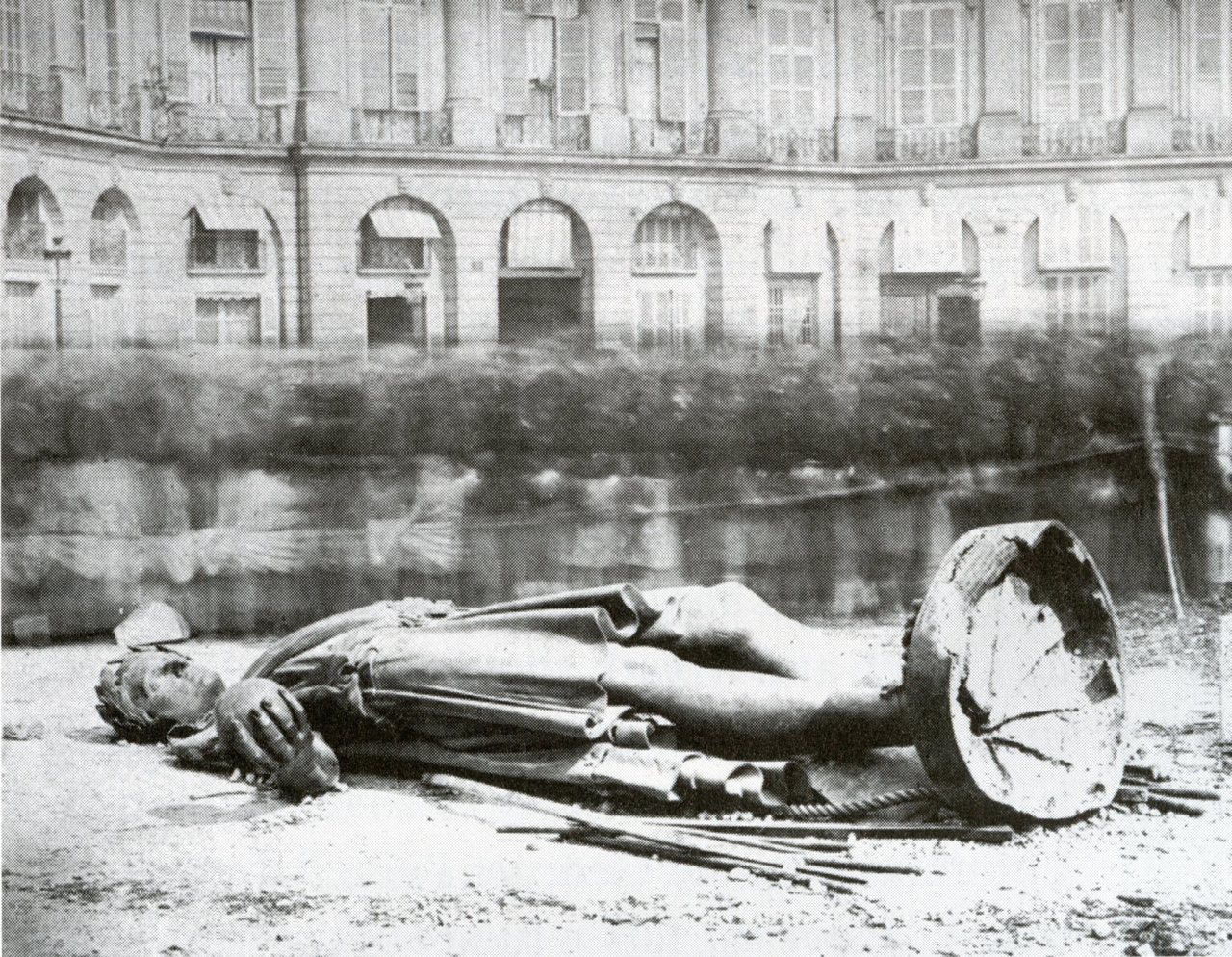

Bruno Braquehais’ main image of the demolition of Napoleon’s column in the Place Vendome.

A man of Napoleonic stature

The third man smiles quite broadly but a heavy moustache blocks this expression. (He looks a bit too genial for a soldier.) While Rimbaud holds his rifle correctly by the butt, shouldering it menacingly – ready-for-action – this man rests his rifle more casually on the ground. This fusil – with bayonet affixed – is almost as tall as its diminutive bearer. We notice a white collar at the third man’s neck; also a watch-chain half-way down his chest: both these suggest some kind of military bureaucrat. We note too that he carries no ammunition, unlike the poet who slings his cartridges to his left in a small lightweight metal case, well out of the way yet easily accessible on his hip. The fact that the third man carries no live ammunition could denote an administrative role in the Communard military structure.

So who is this third man in the plinth-group? I want to suggest that this person who steps forward so authoritatively towards the camera – as if to say ‘I created all this!’ – is the man who actually signed the bureaucratic order which triggered the demolition of the Vendome Column. I want to speculate – more recklessly than any banker – that this small stocky figure with the genial expression and the bushy moustache is none other than Jules Andrieu. Who? (Even some Rimbaud fanatics have never heard of Jules Andrieu.) If I am correct in this surmise then another significant link has been found which makes the identification of the boy-soldier as Arthur Rimbaud much more probable.

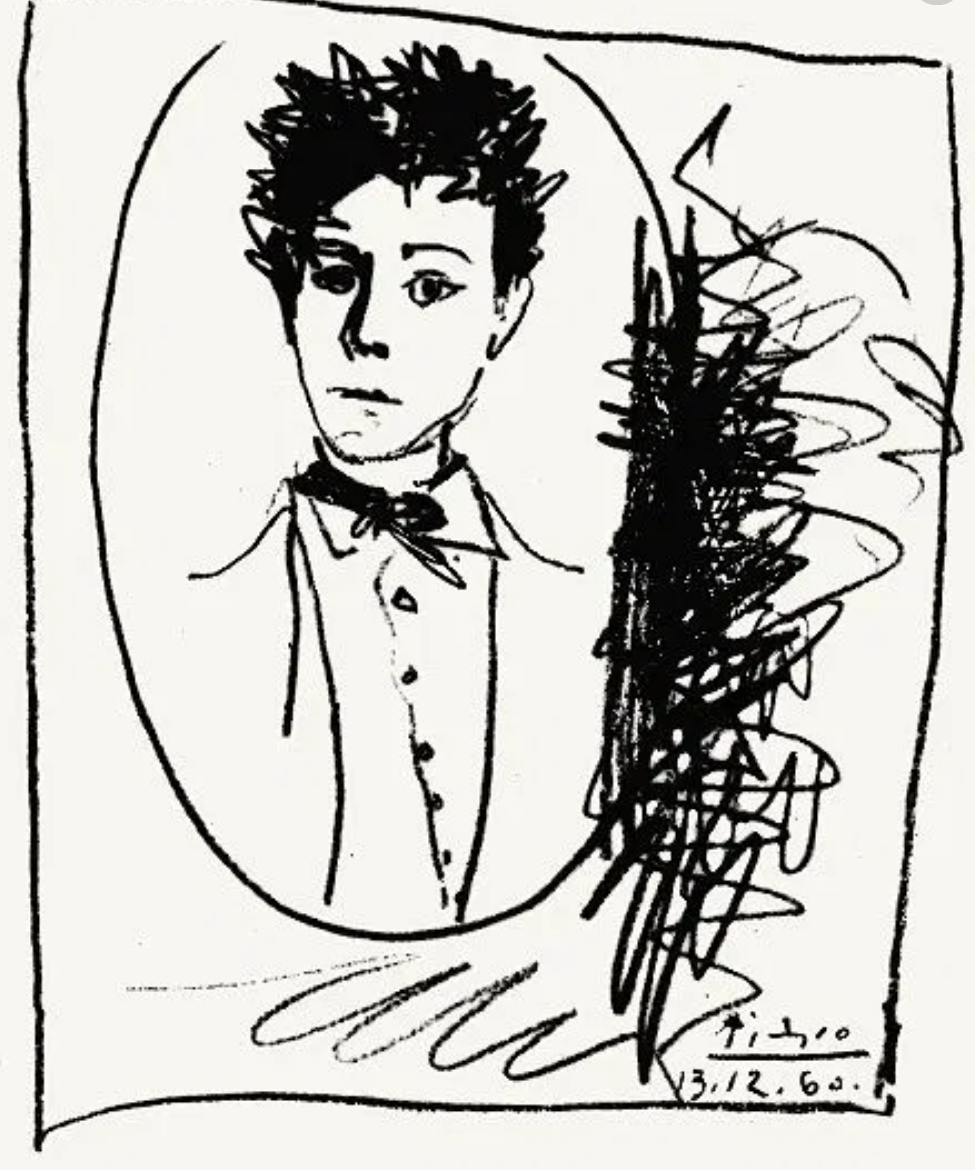

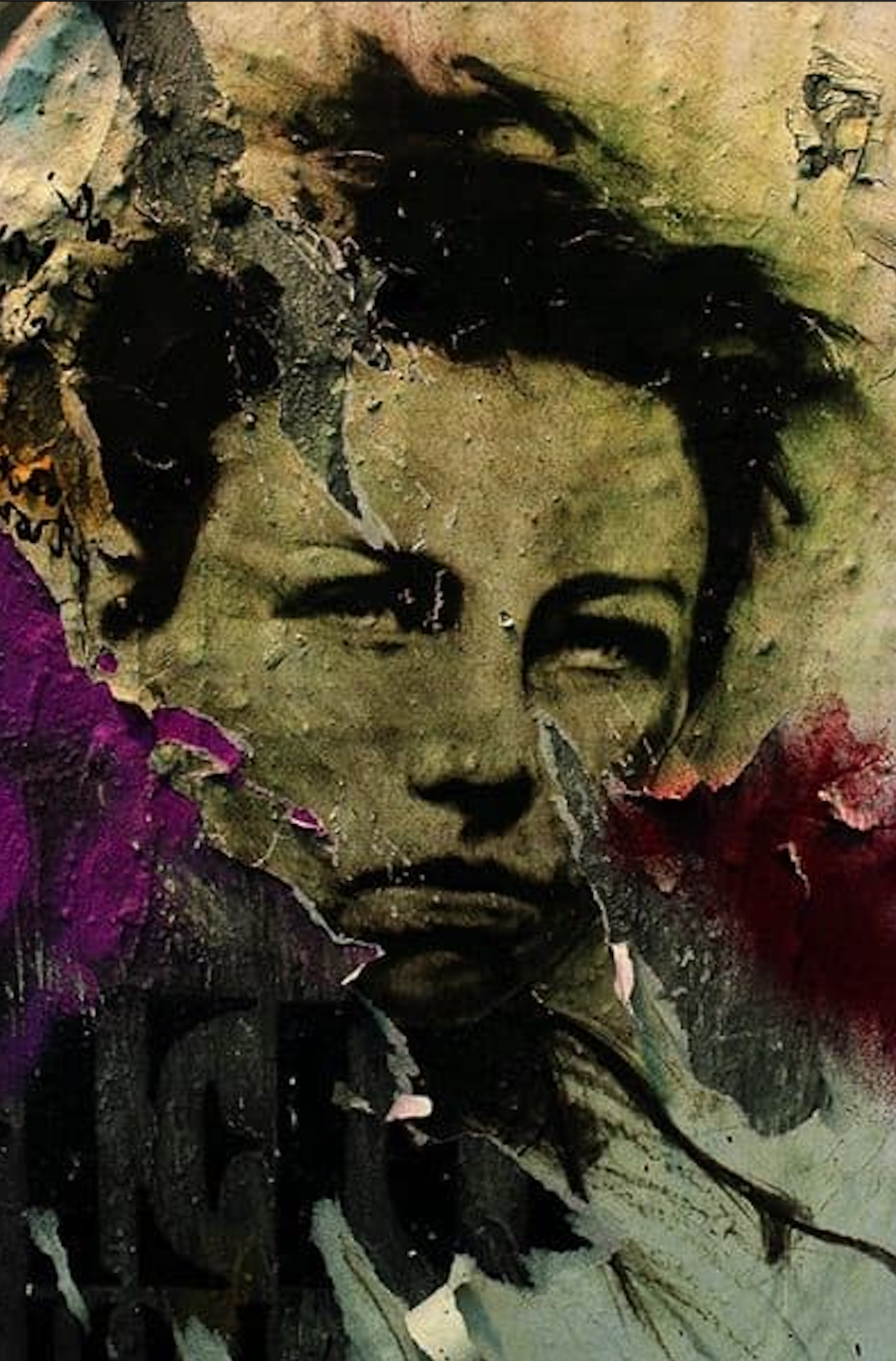

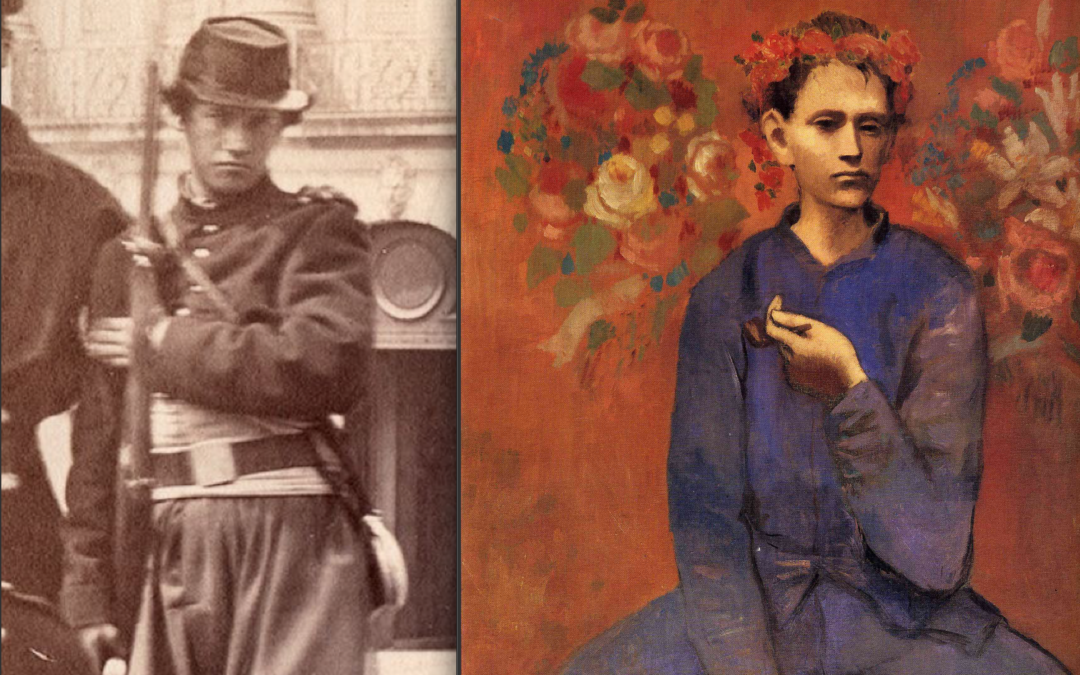

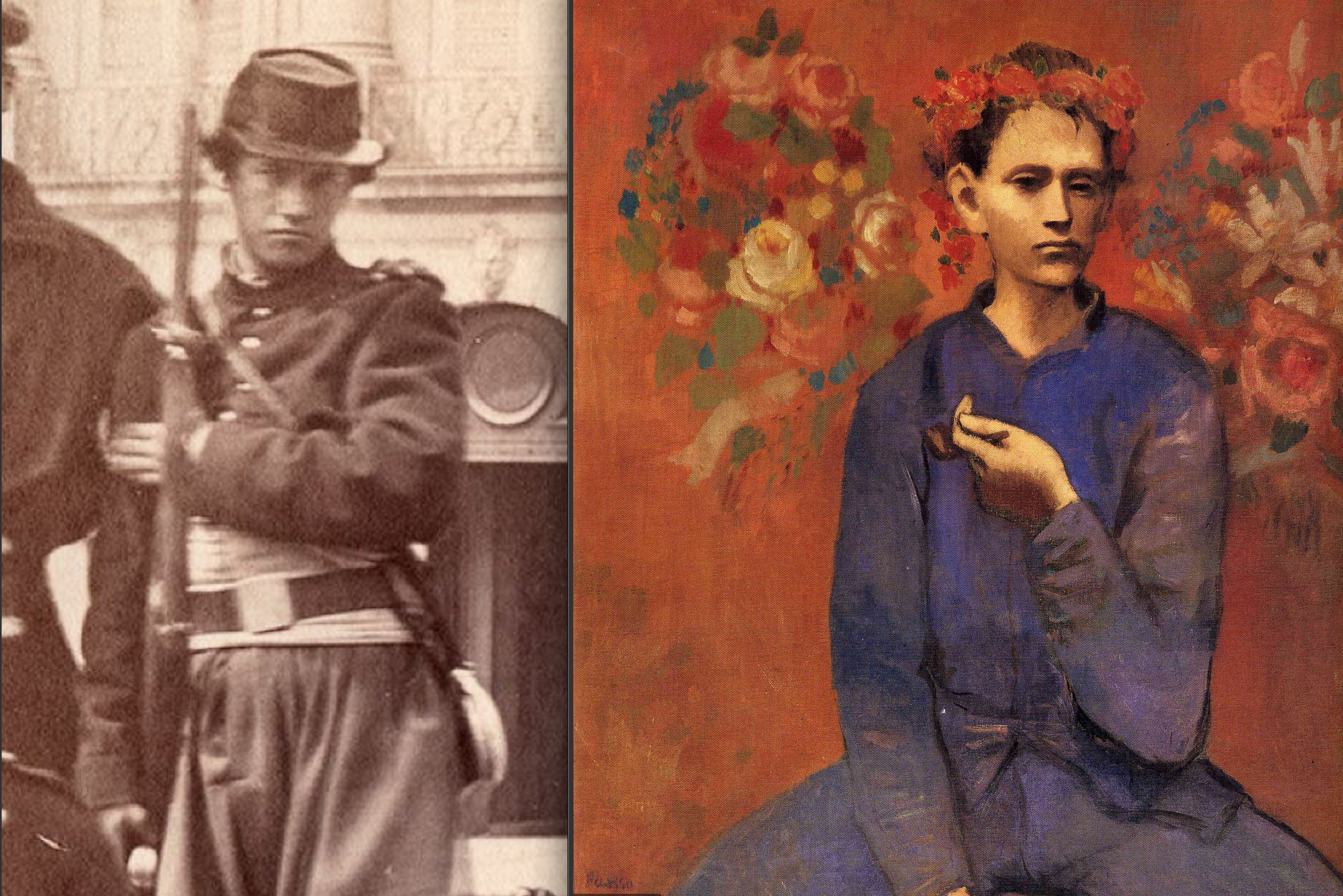

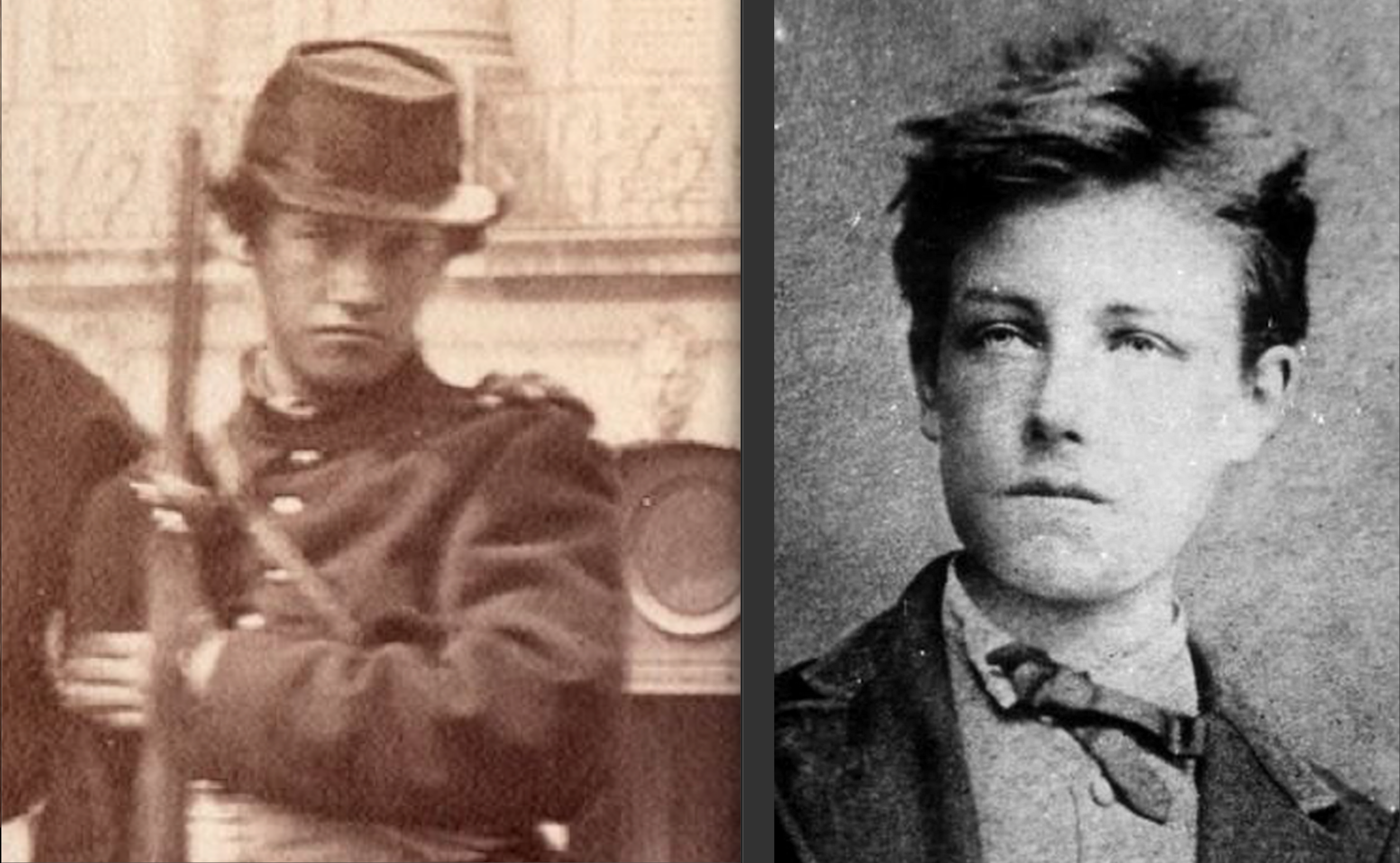

Jules Andrieu. In the studio portrait (left) it is important to note that lighting and camera-angle have flatteringly hidden the prominent and chubby cheeks which are so much a feature of the Place Vendome shot. We are also looking at a younger Andrieu in the studio-portrait. (He appears here to be about twenty-five or so, whereas during the Commune he is thirty-three.)

Jules Andrieu’s photograph of the Place Vendome, post-demolition. Andrieu’s Parisian sequence Disasters of War is a photojournalistic masterpiece, like Braquehais’ Paris During the Commune. It is highly likely that the two photographers – working in a new and very specialized field – knew eachother professionally and even socially.

A polymath and an autodidact

Jules Louis Andrieu was born in Paris in 1838 and he died in exile aged only 46 in Jersey. He is usually described as a ‘short, shaggy-haired man’ who ‘smiles easily’. (We have two portraits of Andrieu and he smiles in both of them, unusual facial language for the time.) Jules Andrieu was something of a polymath and an autodidact (like Rimbaud himself). A poet, a linguist, a teacher, an occultist and a civil-servant, he was also a prolific author and a photographer. Before the Commune he worked for the Paris Prefecture in a fairly subordinate position in the municipal administration. Yet in his spare time he gave free lessons in secondary education to working-class Parisians, openhandedly sharing his passion for poetry, history and philosophy. In 1860 he published Palmistry: a Study of the Hand, Skull and Face. Six years later his History of the Middle Ages appeared. In 1867 followed Philosophy and Ethics. At some point during this period, as a habitue of the poetry cafes of the Latin Quarter, Andrieu met and became friends with Paul Verlaine.

Now, in 1871, the Commune’s utopian reverie begins, and Andrieu, with his altruistic curriculum vitae, is immediately appointed chief of staff of the Hôtel de Ville de Paris. Now he rubs shoulders daily with Verlaine who is elected head of the press bureau of the Central Committee. But it is Andrieu, and not Verlaine, who becomes what Graham Robb describes as ‘ringmaster of the republican Parnassians’. (The ‘Parnassians’ were a post-romantic, pre-symbolist poetry movement probably started by Theophile Gautier. De Banville, Mallarme and Verlaine all belonged to this group which was mercilessly swept away by Rimbaud.) Robb describes Andrieu as ‘an encourager and facilitator’. Robb also expresses the interesting opinion that Jules Andrieu’s poetry is valuable and worth reading. (At this point I have not read him myself and so cannot comment, but Robb’s bibliography mentions two collections both of which will have to be explored, both aesthetically and forensically.)

We know that later, in London, Andrieu and Rimbaud will become extremely close, so close that Verlaine will have an episode of jealous rage about their intimacy. (Andrieu’s contemporaries all hint at his homosexuality.) We also have Delahaye’s testimony that in exile Andrieu becomes Rimbaud’s ‘favourite intellectual brother’. In London, these two banished poets discover that they have much in common, sharing not only the craft of making poems but a fascination with mysticism, folklore and alternative history. In fact, as evidence of the closeness between Rimbaud and Andrieu, as proof of how long their friendship endures, we have the recently-discovered ‘Splendid History’ document, turned up among family-papers by the great-grandson of Andrieu, Alain Rochereau. This is a letter from Rimbaud to Andrieu written on the 16th of April 1874. It is addressed from 30 Argyle Square in London’s Kings Cross St Pancras district. (This is the small hotel where Rimbaud’s mother and sister stayed with him for several weeks while he attempted – rather half-heartedly – to find work in England, still effectively an exile, still unable to return to France.) In the ‘Splendid History’ letter Rimbaud sets out a plan for a visionary and alternative historical text which the poet hopes Andrieu is going to help him publish. (I intend to look at this extraordinary letter in detail in a future essay.) From the dating of this correspondence we know that Rimbaud’s friendship with Jules Andrieu lasted long after the ‘London pilgrimage’ period. While Rimbaud was writing his ‘Splendid History’ letter in Kings Cross St Pancras in 1874, Verlaine was languishing in a Belgian prison cell looking back to 1873 and the crisis in Camden Town. (In fact Argyle Square is only a ten minute walk from Great College Street, where the Infernal Bridegroom and the Foolish Virgin descended into the relational insanity delineated in A Season in Hell.)

The point that I am trying to make here is that contact between Rimbaud and Andrieu – however glancing – might just have been initiated during the seven weeks of the Paris Commune. And it is possible that if that such contact was made Rimbaud might have referred to it in his first letter to Verlaine, the text of which has been almost completely lost, destroyed by Verlaine’s wife Mathilde. We have only fragments of this crucial first letter, so we don’t know exactly what connections Rimbaud used in reaching out to the famous Parnassian. But the tone of his letter is warm, intimate and autobiographical, very different in style to a letter previously written to Banville. It is just possible that Rimbaud – knowing that Andrieu was close to Verlaine – might have mentioned some (even anonymous) contact made during the Commune (when most aritsts making political statements used pseudonyms).

These are necessarily tentative speculations, but how could contact with Jules Andrieu have actually happened?

Jules Andrieu in a second studio portrait (left). Once again clever lighting and camera-angle have hidden the chubby cheeks which are so much a feature of the Place Vendome shot. Both studio portraits would seem to be taken at least eight years before the Communard group-portrait in the Place Vendome.

Hands full of horsepower

It is not difficult to imagine a man like Jules Andrieu spending a lot of time in the poetry cafes of the Latin Quarter. As a man of influence under the new pre-socialist regime his project is to cast a cultural dragnet through the literary underground of Paris hoping to discover some new voice which truly articulates ‘the resurrectionary mythology of the Commune’ (Graham Robb’s phrase.) We can easily suppose that in one of these atmospheric smoke-filled dives he witnesses a young hoodlum called Jean Baudry – or is it Alcide Bava? – reciting the most inflammable verses he has ever heard. This baby-faced soldier-poet in the uniform of the Paris Irregulars is declaiming a seasick poem of mysterious violence. Nautical imagery amplifies an orgiastic nightmare in which the stern of a vessel is rammed in a nauseant assault. As the baby-faced poet howls his Stolen Heart a subterannean gas-lit den begins to sway side-to-side like a drunken ship. (Someone spews quietly in a corner.) Now the mass-hypnosis intensifies with a poem titled The Hands of Jeanne-Marie. As the grim singer chants a hymn of rage to the anger of Parisian working-class women he suddenly seems to become one of them. (His huge red hands flail the shadows as he declaims his republican battle-song.)

More fatal than machines

these hands full of horsepower.

Andrieu is left breathless. Stunned, he has just seen some transgender petroleuese set fire to the fabric of reality, burn down the sky. When the demented recitation finally subsides he goes over to a candlelit table where the young poet sits with a bulky companion who seems to act like a personal bodyguard. Andrieu introduces himself, not as a poet but as a photographer. (Andrieu’s valuation of his own verse has just sunk several octaves lower.) He elegantly compliments the adolescent genius, then mentions casually that the following day, a colleague and close friend of his – the deaf-mute ‘collodion-gunner’ Bruno Braquehais – is planning to capture the demolished Napoleon lying in the rubble of the Place Vendome. Would this young poet deign to appear in the composition? Gustave Courbet has promised to be there.

The young poet gives a surly grin and mumbles something non-committal. (He enjoys the street-game of pussyfooting around.) Andrieu, baffled, plays his ace-card:

‘I’m the one who signed the demolition-order!’

The revelation has no impact. There’s zero response. An infernal adolescent grimace remains firmly superimposed on the baby-face.

Doomed brother-Communards

Like the Commune itself our dream has been brief.

If the third man is really Jules Andrieu then we know that the plinth-grouping is intentional. If Jules Andrieu as-it-were introduces Rimbaud then the symbolism of Braquehais’ masterpiece is complete. Now we see ‘the resurrectionary mythology of the Commune’ expressed by the mighty youth of armed revolution, backed-up by his best friend (Hercules of the warm-heart) and introduced to the world by the Communard chief-of-staff.

To conclude.

I have a notion about the crowbar, that crowbar so obviously placed as a prop right next to the third man, the emblematic and phallic crowbar which screams ‘I toppled a military dictator. Deal with that!’ I want to speculate – if possible without crashing the literary stock-market – that it just might have been Jean-Arthur himself who suggested to Andrieu the employment of some ugly stage-furniture. As the poet about to invent literary symbolism it would have been a nice ironic gesture on the poet’s part to provide the miniscule Jules Andrieu with the lever which brings the Second Empire down. That crowbar gives Jules a bit of extra weight, makes a small man seem a lot more substantial.

It’s just a vague suspicion.

But isn’t life itself a second-guess?

Andrieu’s crowbar is the symbolic lever which has turned the Second Empire upside-down.

Recent Comments