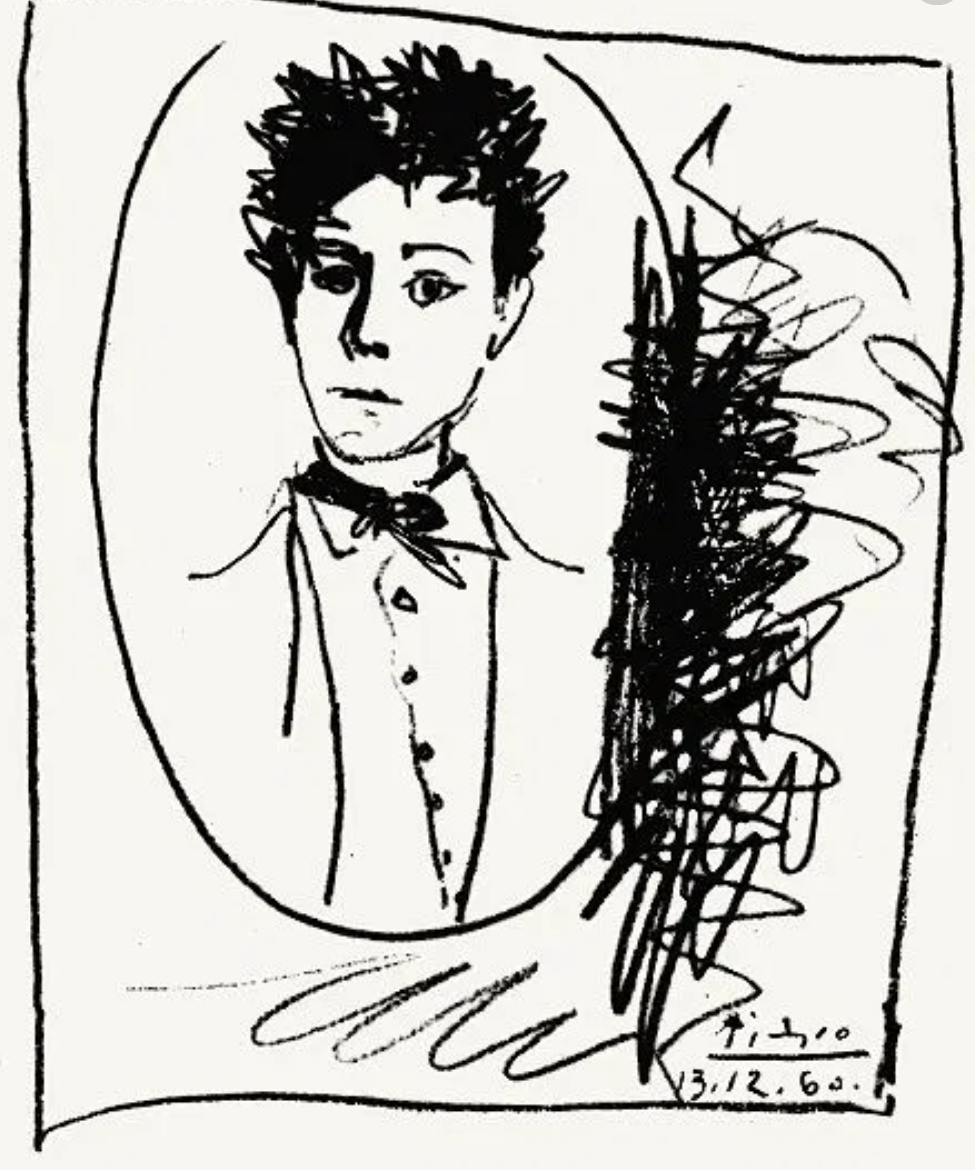

Picasso’s sketch of Rimbaud

No paper-trails

Based on Rimbaud’s movements in the spring of 1871 there is one possible chronological objection to the authenticity of the Place Vendome images. This argument suggests that the poet is unlikely to be in Paris on the 16th of May for the demolition of Napoleon’s Column because one of his date-stamped letters proves that on the 15th he’s a hundred-and-fifty miles away in Charleville. However, though rail links are obviously compromised at this time, some of Rimbaud’s biographers believe the ‘man shod with the wind’ could just have managed to be in Paris on the 16th. And yet, as we will see, this is not absolutely essential to the argument for his appearance in the Braquehais images.

There have been many misunderstandings about Rimbaud’s activities in April and May of 1871 partly because of the internecine chaos sweeping northern France at this time. Sequential precisions fly out the window as two separate governments begin a fight to the death over Paris. Then – as I’ve just mentioned – a question-mark hangs over transport options as train timetables vaporize in the ultimate lunacy of a civil war. And finally there’s the biographical stumbling-block: Rimbaud doesn’t leave a paper-trail. Intense and infrequent, his letters reveal next to nothing about his day-to-day affairs. (Arthur Rimbaud wasn’t on Facebook.)

Jean-Luc Steinmetz, perhaps Rimbaud’s most illustrious biographer, himself a French poet of distinction, clearly defines the poet’s timetable during the crucial seven weeks of the Commune. He writes:

‘There are two strongly circumscribed periods of time – April 17th to May 12th and May 15th to May 28th – during which he could have gone to Paris and demonstrated his solidarity with the insurgents.’

(Arthur Rimbaud: Presence of an Enigma, p.59)

The Vendome Column about to come down

Postliminary images

The Vendome Column falls on the 16th of May. We realize from Jean-Luc Steinmetz’ calculations that Rimbaud can indeed witness the actual demolition if he races to Paris the day after writing ‘the letter of the Seer’ in Charleville on the 15th of May. In this scenario he rides a train part way to the city – perhaps to the outer suburbs – slips through Versaillais lines and enters the metropolis. However, against a backdrop of collective pandemonium this journey is more likely to take a few days. Which means that Rimbaud cannot be present when the column comes down on the 16th of May. (Though Steinmetz deems it possible.)

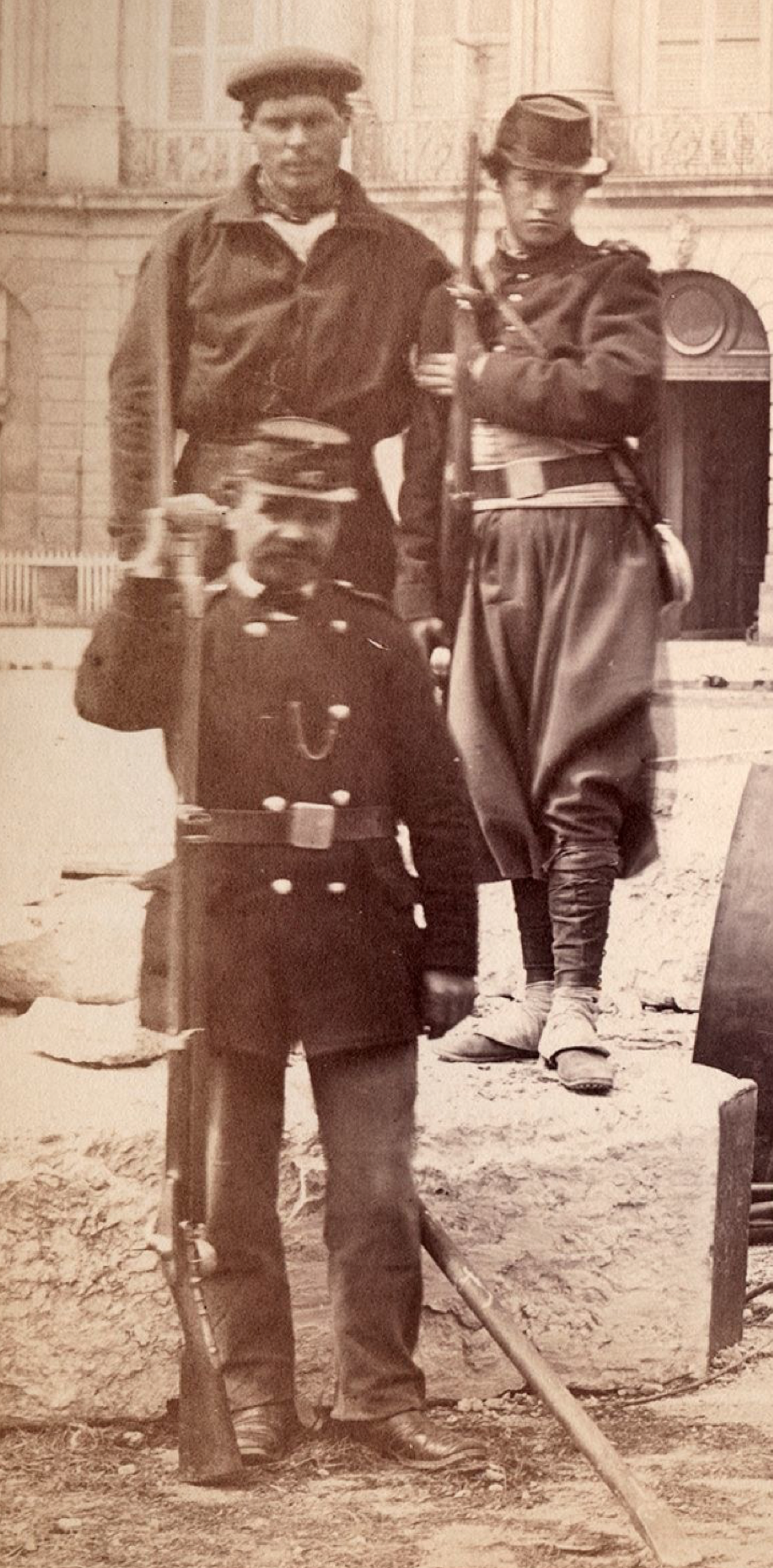

But another possibility opens up if we conservatively suppose that Rimbaud gets back to besieged Paris on either the 17th or 18th of May. (We know how frantic he is to be there. In a letter dated the 13th of May he says that ‘mad anger drives me towards the battle of Paris where so many workers are dying as I write to you now.’) Arriving on the 17th he misses the climactic moment of the Commune by one day. Yet though this disappointment matters greatly to him it doesn’t matter at all to us, because of course the Vendome Column still lies across the square; and will continue to lie there for many long months, until 1873 in fact. And the poet is still in time to be captured by Bruno Braquehais because his photographs are not taken on the 16th! The Braquehais images are clearly postliminary. Every detail of these images betrays the fact that they are carefully orchestrated group-portraits, artificially composed and thoroughly choreographed. The Braquehais photographs are taken several days after the actual toppling of the Emperor. It’s a mistake to challenge the authenticity of the Braquehais images based only on the date of the actual demolition.

The actual fall of the Vendome Column on the 16th of May, 1871

Smoothly Driven

There exists one photograph – of unknown provenance – which does seem to record the immediate aftermath of demolition. We note that in this shot a vast crowd of soldiers (and maybe civilians) is in a state of great turbulence and excitement. Here no one has dared to ask the mob to hold still through a long exposure-time. Naturally the result is a blurred sea of forms in which we can make out the ghost of a face here and there. Hundreds of people appear in this composition, ranks upon ranks retreat into the background. In the foreground there is debris and dust everywhere. From extreme left to extreme right people jostle against a crowd-barrier in the form of a long rope slung on stakes. We can safely assume a circular multitude completely surrounding the military idol. If it weren’t for the stout line holding them back this excited rabble would be dancing on the fallen god. Almost certainly this is the 16th of May. As we look at this image we can almost hear the Marsellais roaring out a thousand throats.

There is nothing composed about this raw image. (If Rimbaud is here we certainly can’t see him.) Compare this turbulent, seething photograph with the relative tranquility of the Braquehais image and immediately we understand that the Rimbaud group-portrait is shot several days after the event, when the fuss has died down, when the mob has dispersed, when the first delirious excitement has subsided.

So, erring on the side of caution, if we allow a driven Rimbaud four days to make the difficult journey to Paris, this means that he arrives on the 17th or 18th of May. Now the movement of the clock runs smoothly and easily. Now the chronologies work properly. Because, before the beginning of Semaine Sanglante (which commences on the 22nd of May) there exists an interval of almost a week during which Bruno Braquehais has the opportunity to set up a complex photgraphic procedure; and Arthur Rimbaud has time to get to Paris.

The fallen idol of military France. (Image of unknown provenance, thought to be taken on the 16th of May 1871.)

The handsome renegade of the Place Vendome stands as tall as he can, the franc-tireur incarnate. With his rifle-butt raised in his right hand and his bayonet pointing at God’s blue sky he challenges all the basic premises. Europe is going to hell and has to change. As poet and freedom-fighter he dreams of transformation. The free-state of Paris will show the rest of the world. A new order of cosmic socialism is coming.

Beside him stands the one true friend he can trust. Everything seems possible at this moment. Holy Paris may be encircled with devils, just as Troy was surrounded long ago. But he is the Trojan prince who has slept with Beauty. And now – like Hector – he guards Her under seige. He and his companions may be outnumbered, they may be encompassed by demonic enemies. But his muse is immortal. She cannot die.

In my next piece I plan to analyse the triumvirate, to decode the mystery of the Third Man who stands in front of Rimbaud and his nameless friend.

Please stay tuned!

The enigmatic triumvirate of the Place Vendome. The ‘Third Man’ stands closest to the camera, smiling.

What we see in several photographs is the figure of the toppled Napoleon. What we don’t see are any fragments of the column. If you look at the wonderful illustration (a lithograph?) above, the artist–likely an eye-witness–has recorded the crumbling of the column into at least three fragments as it is pulled down. Where are these fragments in the subsequent photographs? Hauled away, certainly, and perhaps used for the barricades. Clearing this heavy debris would take days. Rimbaud hears of this momentous event and returns sometime before the 21st of May and is convinced by friends to flee before the massacres begin.

Certainly there’s been a clean-up before Bruno Braquehais gets busy with tripod and mobile darkroom. Recycling into barricades is very possible, good point. Remember, the Versaillais are at the city gates and these better-armed bourgeois take no prisoners (as someone else said). Rimbaud is standing in the dragon’s mouth, in the lion’s den, he has only a few days to get out of town alive. That lithograph (?) is quite a whirlwind of destruction isn’t it? Quite Shivite, very Rimbaud!

Also, again looking at the lithograph, note the direction in which Napoleon is falling and its distance from the base of the column. In the photographs by Braquehais, the statue of Napoleon is directly beside the plinth. It is apparent that Napoleon has been dragged from his landing place to the plinth for better photographic effect. In the non-Braquehais photo we cannot see the plinth, but that may merely be due to the way the photo was cropped. Interesting, too, is the fact that, if the lithograph is accurate, there was what appears to have been a cube-shaped brick base atop the plinth. It was apparently demolished before the Braquehais photos. It is doubtful that all of this could have been achieved in the space of a day or two.

Napoleon would have fallen near the perimeter of the square but as you say he has been dragged to the plinth for effect. The Braquehais is carefully composed and this labour-intensive management of props and scenery provides the important time-lapse which allows Jean-Arthur to arrive from Charleville. All perspectives noted (and to be recycled, with your permission). On to the splendid cities!