Arthur Rimbaud: Love’s To Be

The Place Vendome image side-by-side with the Carjat studio portrait. Note that Rimbaud tilts his head down on the left, making his nose look wider than in the Carjat, where his head is slightly thrown-back, a standard studio technique to achieve exactly this more aristocratic look.

Christmas on Earth

I’m chanting – eyes closed – under my breath:

Love’s to be.

Over and over I’m breathing a spell, letting it drift in my bloodstream, work in my spine, cycle over and over:

Love’s to be!

Slowly I surface from five times deeper than sleep. The world seems more tranquil. Has it been reinvented? I hear the old-fashioned sound of children at play on the green, how quaint, how charming. They should be locked up in classrooms. Isn’t that so?

All schools should be under trees. (Who said that?)

The sun is shining. I look up. For the first time this century vast skies are clear of contrails, those white cancellations which cross-out the blue, which slash our atmospheres horizon-to-horizon, the whip-scars of our self-hating civilization. Has the selfish giant who writes human destiny – out of limited identifications – gone to sleep? Has he swallowed his own toxic marker-pen? For the first time this century clean turquoise skies are clear of poisonous transports, thundering machines. The jets which service our restlessness have been grounded. The big planes which relay jetlagged industrialists back and forth across the international dateline sit idle near runways where grass begins to grow.

Should I weep?

These big dreamy skies make me think of the eyes of Rimbaud. In his eyes we see the light of the oversoul, in his eyes we see the possibility of ‘Christmas on Earth’. Rimbaud dreamed that we could ‘reinvent’ love.

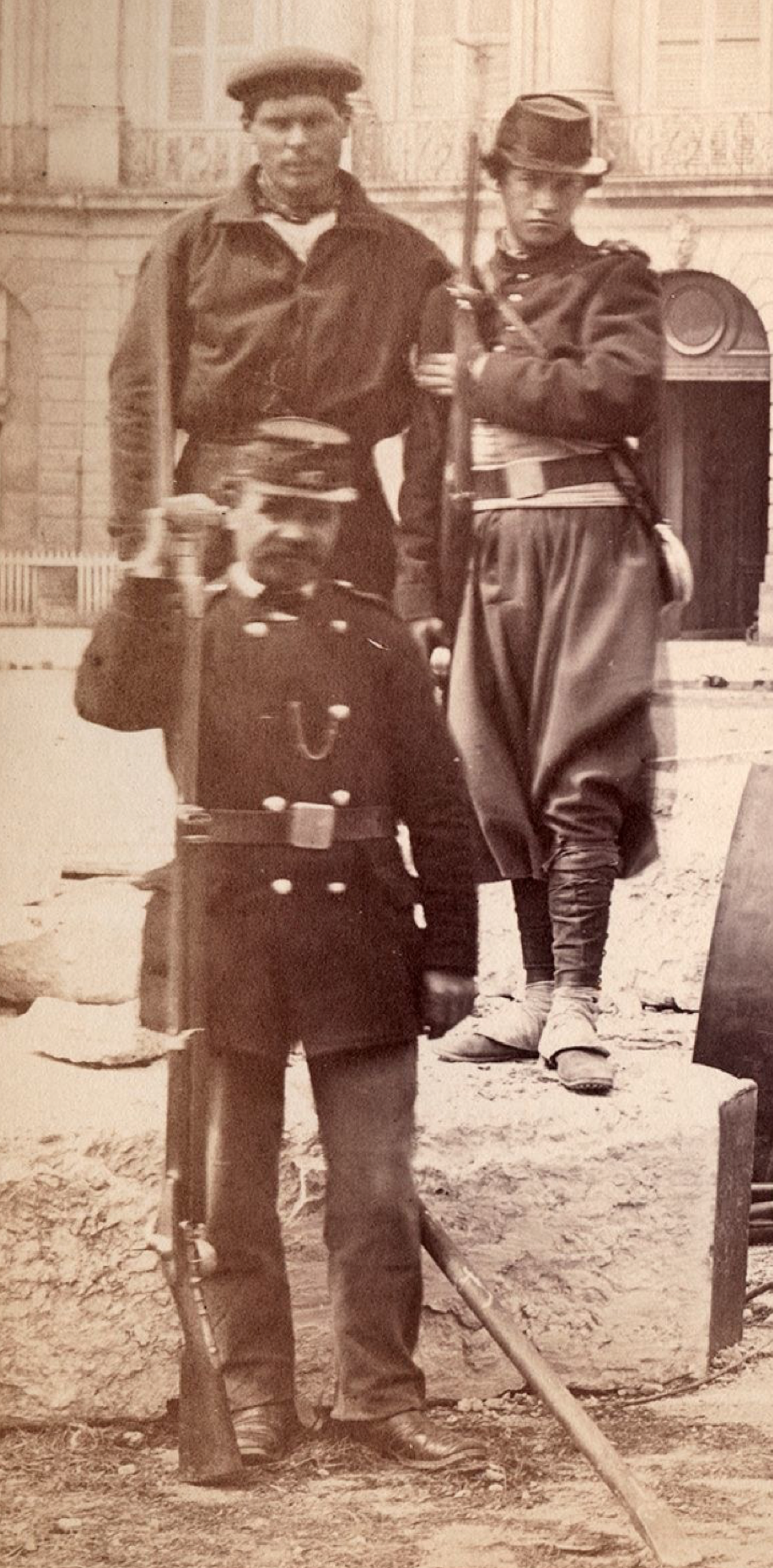

Bruno Braquehais’ main image of the demolition of Napoleon’s column in the Place Vendome. The Communard Rimbaud stands on the plinth nearest to Napoleon, scowling into shot with his feminine baby-face.

After the Pandemic

Our world has changed in just a few weeks. In March we were living under a capitalist system, now in April some sort of quasi-socialist dispensation is in place. With world-populations under house-arrest many are saying that democracy has died. with so many businesses destroyed by self-isolation Covid-19 could be the beginning of guaranteed basic income. (We’re seeing ramped-up digital surveillance; mobiles are fast becoming pocket-informers.) It would seem that governments are trying to act selflessly, putting the sick and the elderly first, funding vastly-accelerated medical research.

Yet the heartening scenario of what humans can do together is overshadowed by the question of what remains to be done. When this pandemic is beaten the real work begins. One in ten people on this planet perishes from drinking foul and contaminated water. (That’s more than all the wars put together.) Seven-hundred and eighty-five million souls slake their thirst each day with stagnant filth, refresh their children from a putrid source. (Can anyone imagine fighting C19 fevers with ditchwater?) Yet suddenly, when the developed world is threatened, governments are trying to act responsibly. If such principled actions and mobilizations had happened before the pandemic struck we might not be in the present apocalyptic situation.

Capitalism is flawed. The price of an individual claiming his or her freedom is fiscal slavery for the collective, this we know. It is scientifically proven in Das Kapital. On the other hand, socialism also is broken. Marx based his theory of rapid social change on Hegel when he would have done better to use a Darwinian model. Nature evolves gradually over time. Revolutions are sudden spikes of chaos creating vacuums of power to be occupied by monsters and tyrants. Revolutions have changed everything except the human heart.

Rimbaud doesn’t like what he sees as he gazes at us from the Place Vendome.

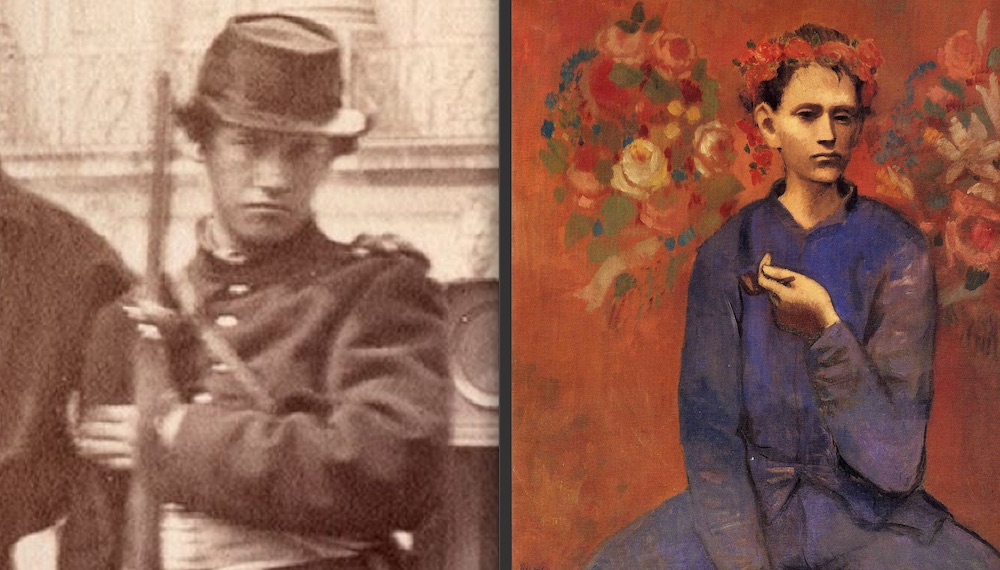

Picasso’s Boy With A Pipe alongside Braquehais’ image of Rimbaud in the Place Vendome. In my next essay I will be investigating Picasso’s most arcane portrait, said by Sir John Richardson to be based on Verlaine’s poem about Rimbaud, Crimen Amoris.

Overcoming the Plague

Arthur Rimbaud dreamed not of a revolution but of something far more impresssive: a transformation.

The children sing to you: Change our fate, overcome the plague.

Cosmic socialism could not persecute the Falun Gong simply because their disciplines are non-reductive. And altruistic capitalism could function in the way medieval monasticism related – comfortably – to the marketplace. Yet while nature transforms and man’s possibilities are infinite, we’re throwing away our most precious resources. The loneliness of the modern world means that the streaming of pornography is the only solace for isolated males addicted to self-stimulation. The internet is hypersexualized; it is 60-70% pornography. Dirty servers – euphemistically called ‘the cloud’ – running on carbon-based fossil-fuels contaminate our skies (and our souls, in some cases).

Love is not here yet.

It’s on the horizon. It’s recently come a bit closer, like Rimbaud himself.

Unconditional love is within reach.

Love’s to be!

AAD in front of the House of Arthur Rimbaud in Kings Cross St Pancras, Central London. Rimbaud lived here for seven or eight weeks while writing Une Saison en Enfer in 1873. AAD’s epic poem Vale Royal unlocks the psychogeography of this mystic zone of London to which many visionary poets have been drawn, among them William Blake, WB Yeats, Shelley and Chatterton, who (dying at 17 in Kings Cross) can be considered the English Rimbaud.

A Dark Place

I have travelled with Arthur Rimbaud for many years. He changed my life in a supernatural manner when I was in a dark place, turning twenty. Two decades later I stood on the stage of the Royal Albert Hall in front of five-thousand people to recite the prologue of an epic poem which had taken twenty-three long years to write, years spent living on the streets of London, years spent meditating in derelicts. That poem, Vale Royal, was – in a sense – dictated to me by Arthur Rimbaud. (I will go into this elliptical history in a later piece.) In another – more famous – example of theophanic intervention, Paul Claudel was transformed on Christmas Day in 1886 when Rimbaud seemed to lead him into Notre Dame Cathedral. There – as an atheist – he went through a spiritual initiation which made him the greatest Catholic poet of the 20th century, the man who visibly stood up against the Nazis, condemning them as ‘wedded to Satan’, ‘utterly demonic’.

Do I think of myself as a Rimbaud scholar? Yes, but my approach to his biography is less individual, more universal. I base my understanding of this poet at archetypal levels. Over the years I have come to regard his emergence onto the world-stage as nothing less than mythical. His unique presence in contemporary world-culture makes him a Mighty Youth: an Absalom, a Hermes. I see him as messenger, winged runner between dimensions. Rimbaud is an interpreter of the multiverse, decoding the realities folded into our world. For all these reasons – and many more – I believe that this Christlike poet has appeared in the Place Vendome for revelatory purposes. The greatest Frenchman (like the greatest Englishman, William Blake) has a message for us in the time of plague.

Through the Spirit we go to God. Heartbreaking misfortune.

Rimbaud began with a doctrine of excess, driving himself at any cost to become a seer. He ended – only three years later – by saying the words above, his wonderful irony coming to bear on the fact that our five senses are circumscribed and limited but human superconsciousness is infinite. Rimbaud is teaching that death – in the context of the multiverse – represents the supreme misunderstanding. He says that death is a false interpretion based on partial data and incomplete experience. Yet the ‘absolutely modern’ seer adds that the manner of our dying is very real; and he asks us not die miserable deaths.

A bad death would be one where the meaning of life dawns too late; where an ego-driven individuality understands only on the threshold of the unknown that if unconditional love had allowed forgiveness – and freedom! – an experience might not have involved monotonous repetitions.

The plague could come back if we don’t transform.

Chant the Aquarian prayer with me:

Love’s to be!

Rimbaud in the Place Vendome with his nameless friend (who places his left hand on Rimbaud’s shoulder). The small man in front of Rimbaud may be Jules Andrieu.

Recent Comments