Rimbaud: In Arthurian Country

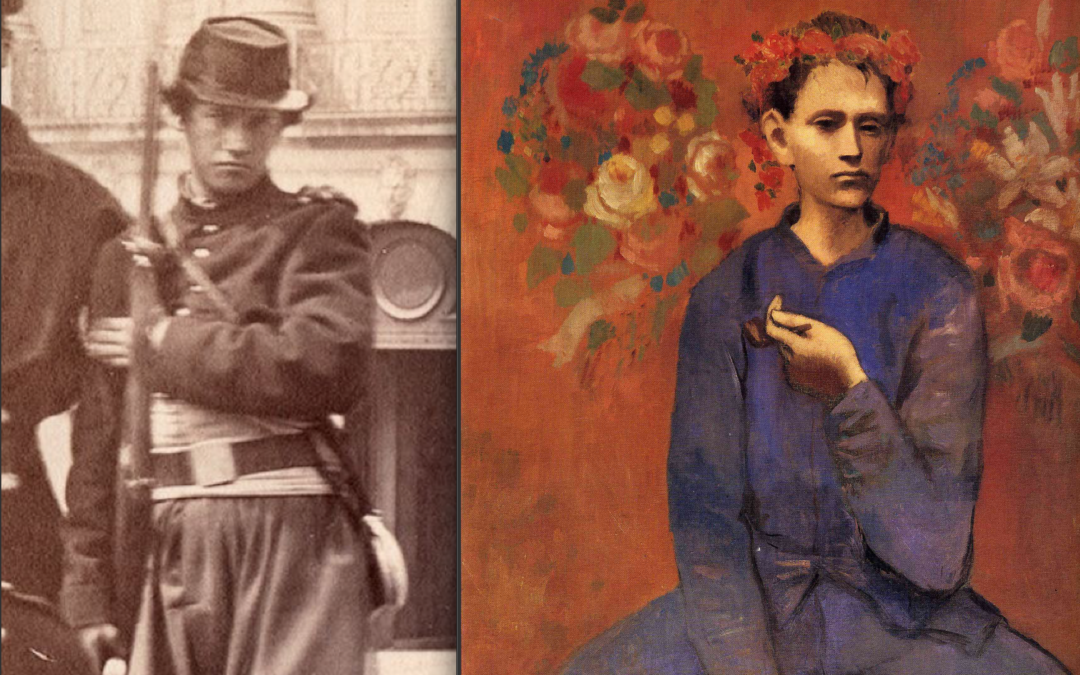

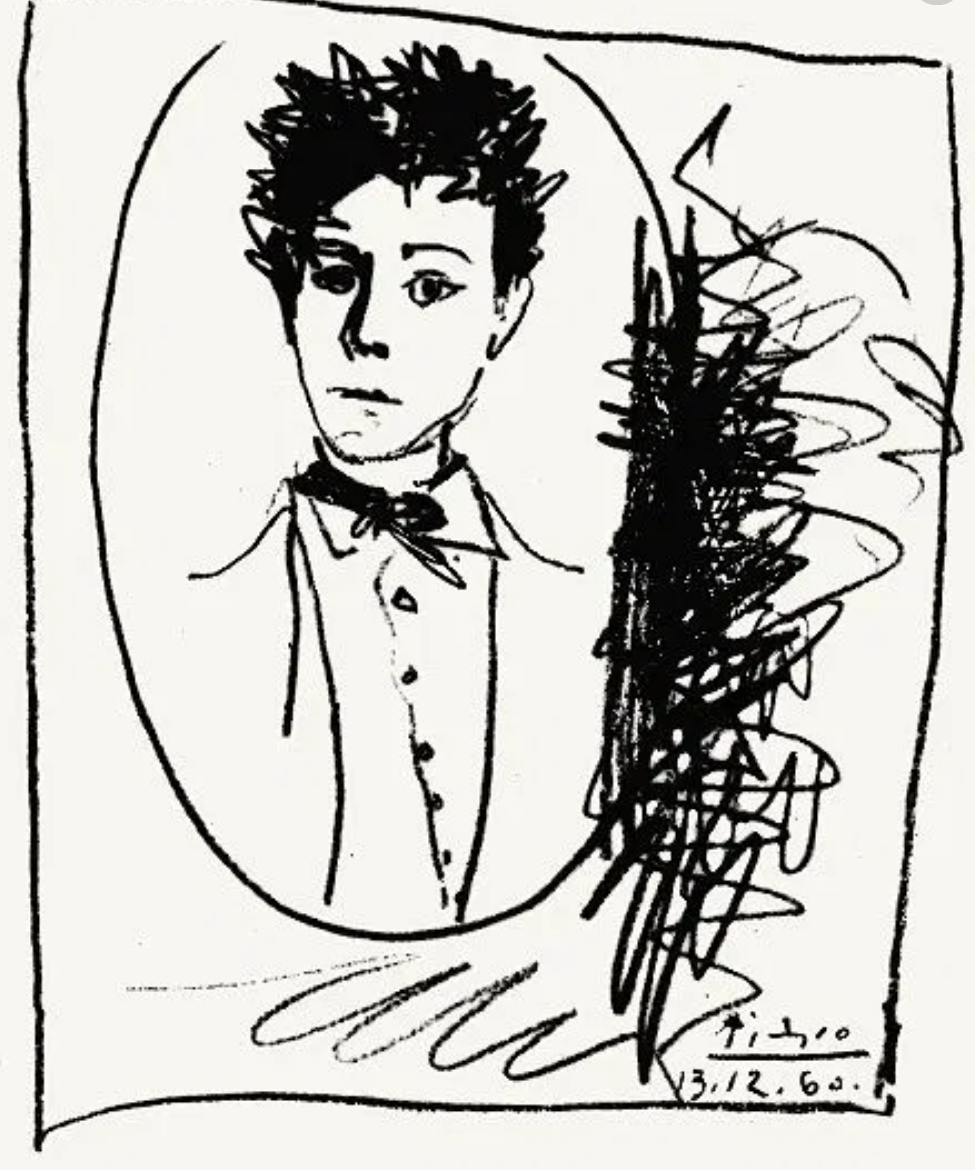

The soldier-boy of the Place Vendome (left) and (right) Picasso’s enigmatic portrait Boy With A Pipe, believed by Sir John Richardson (the painter’s best biographer) to be a portrait of Rimbaud.

Virgin Soldier of the Place Vendome

A soldier-boy stands in the Place Vendome. A mighty youth with a gimlet stare personifies and incarnates revolution. The shockwave of his gaze is intense. It’s the look in the eyes of an angel on the burning lake. It’s a blast of white-hot rage which seems to say: Here’s faster-than-light vengeance for centuries of enslavement. Here’s instant justice, death to your martial gods. An androgynous nineteenth-century Che Guevara glares nastily out of the Place Vendome, personally overseeing the destruction of the Imperial cosmos. We are looking at some ‘marvellous boy’ who has just masterminded the coup d’etat of all time. (We don’t even really see the eyes but the black fire coming out of them is unmistakeable.)

We also observe ultra-narcissism here. (Note the carefully-cloned attitude in both images. The second Braquehais is reproduced below.) A very self-consious young man has been spending a lot of time in front of mirrors recently. He’s been double-checking the validity of his self-presentation with great care. We detect massive arrogance in his bearing, his assumption of the role of nemesis to all power-structures; but we see also the vanity of some brand-new recruit who has only donned his war-uniform in the last few weeks. Whoever gazes out of the Place Vendome – aged roughly sixteen and a half? – we sense he’s quite new to the business of insurrection. He’s putting on his grimmest face for the camera.

Yet this is no simpleton boy-soldier proud of carbine and tight-fitting kepi. Here we seem to observe some Dostoyevskyan Raskolnikov ‘stepping over obstacles’ as he rises up rapidly through the ranks, ready to wade through blood, armed to the teeth. Or we could be viewing some obscure corporal singled-out for valour and fanaticism. This young man on full display has about him the aura of some future general. (That familiar Napoleonic-Hitlerian profile.) This virgin-soldier – whoever he is – has been chosen to epitomize the symbolic dimension of the ritual being performed in the Place Vendome. His solemn, standardized deportment and demeanour, his lasering look and his stance with ‘left-foot-forward’, drive the whole composition powerfully. He is the essential presence in an epic group-portrait. (There are echoes here of Delacroix and Jacques-Louis David. The canvas of Braquehais has certainly been planned with the mythical, legendary and historical in mind.)

Arthur Rimbaud as Paris Irregular during the Commune of 1871.

Battlefields of the Spirit

Someone has consciously made the decision that the ship of revolution needs a figurehead. But who stands in the Place Vendome as the ‘figure on the prow’ (as the French expression translates)? I propose that the stern-featured rebel-angel vaunting over the fallen Napoleon is none other than the poet Arthur Rimbaud. I propose that if the soldier-boy on the plinth is not him then the poet must have had an unknown twin-brother who joined the Paris Irregulars in May of 1871 (when Rimbaud is supposed to have done exactly this). And if this outlandish theory collapses (like the Vendome Column itself) then in desperation we can only suppose that the poet’s occult studies in the libraries of Charleville somehow suddenly accelerated to the point where he was able to project his doppelganger into besieged Paris at will.

I admit that such theories are too far-fetched for me. I also confess that hair crackled on top of my skull when I – accidentally – enlarged the main Braquehais image from a thumbnail and saw the face of the great poet of France in a flash. There was no tentative moment at all, I experienced immediate recognition! Later, the filters which exclude the impossible kicked-in, and ‘It cannot be Rimbaud‘ and similar assumptions surfaced. (But not for long.) My very first glance proved fatal to me because it removed all possibility of long-term doubt. Yet my own subjective and automatic faith is irrelevant. Rimbaudian experts will have to decide whether new images of the poet have miraculously – and very unexpectedly – emerged. Where this process will end is hard to say but I am convinced there has definitely been a beginning. Perhaps if Rimbaudians worldwide unanimously wish it Napoleon will be demolished for a second time and the poet will be appropriately remembered in the Place Vendome. (A sacramental crystalline obelisk with no ‘dot in the sky’ might best serve. Arthur Rimbaud is already in the stars.)

As he faces us from the Place Vendome a brave footsoldier is marching towards a battlefield. He has seen terrible carnage in the Rue d’Babylone. (Most biographers are agreed that Rimbaud was sexually assaulted in the Babylon Barracks very shortly before Braquehais’ photograph was taken.) But the poet is marching on towards an even more traumatic event: the spiritual battlefield of A Season in Hell. Written in 1873, only two years after the demolition of Napoleon’s column, Rimbaud’s nekyian masterpiece shows us his own personal Waterloo. (Yet clearly the battlefield he describes in his short prose-poem is actually situated inside every one of us: this is what makes the work so universal.) Only two short years after the Place Vendome the poet faces the culminating crisis of his life. Though we can’t be quite certain exactly what he thinks about the outcome, Rimbaud seems to tell us that he loses this great fight. Apparently he emerges empty-handed from the battlefield. He wins nothing and loses everything. His pride dies but he still does not love God. (So he says.) In one interpretation of A Season in Hell the poet cannot differentiate between God and Lucifer. Why? Because as he looks back at all his magnificent superstructures, his holy cities of bacchanalian happiness, his good – as revealed by the devil – he sees that only evil was generated in the world. He marched in cold blood over too many ‘obstacles’. He pushed too hard and he assumed too much. He said in his pride: To a good man all things are good. But he wasn’t good enough. (In his own opinion.) Now – as he tells us in A Season in Hell – he falls back to earth from his pedestal of transcendence. Now he crashes down from the sky of human conceit. And admitting the truth of his unholiness he finally breaks the demonic code and exposes the self-esteem which fell for false promises. (The devil is such a humanitarian!) Yet he still won’t acknowledge the Christian God who punishes him now with nervous breakdown and near-madness. (As he richly deserves, he informs us.) Thus God becomes the devil and vice-versa. And there is no vision at all, just the sense that human existence is a meaningless farce. He is left with nihilism and fragmentation.

Two years after the Place Vendome, in the loft of a grim farmhouse (in a place called Rocks) Rimbaud takes on the cosmic mystery of the problem of evil: and comes up with no solution. (The very name Roches seems to hint at some desert for the tempatation of a St Anthony.) When the spiritual battle is over Arthur Rimbaud is left speechless; and the poet remains mute for the rest of his life. Rimbaud cannot say, as Goethe says after the battle for the soul of Faust has taken place:

Evil is that force which constantly wills evil but against its own will ends up doing good.

At this point Arthur Rimbaud has no such faith. And that’s why the poet is an existential saint. His terrible silence is his gospel of Nothingness. He is like some Nietzschean superman who overcomes himself yet reveals no new dogma. (Example alone is efficacious, he seems to say.) And precisely this absence of evangelizing in the French poet is what makes Rimbaud so appealing to agnostics – even to atheists – many of whom have found something in his Nothing. One very great attraction lies in the fact that Rimbaud says clearly and squarely: I do not know. This humble admission, this negative testament – coupled with his transcendental verse, some of which is profoundly religious – makes Rimbaud the international poet-laureate: quoted in hip hop, studied in academe. Here is the purest European poet since Dante. Rimbaud is both high-brow and low-brow. Ultimately Arthur Rimbaud is no-brow. He takes poetry out of the study, liberates poetry from the library and restores her to some primordial countryside.

Here is his early Sensation (in my translation).

On blue summer evenings

I’ll walk the trackways

over stubbled grass

needled by the wheat.

Daydreaming, I’ll feel

the coolness at my feet

letting the wind bathe

all of me, bareheaded.

I will not speak;

I will have no thoughts.

Yet infinite love

will mount in my soul

And I’ll go very far

like a vagabond

across the country

happy as if with her.

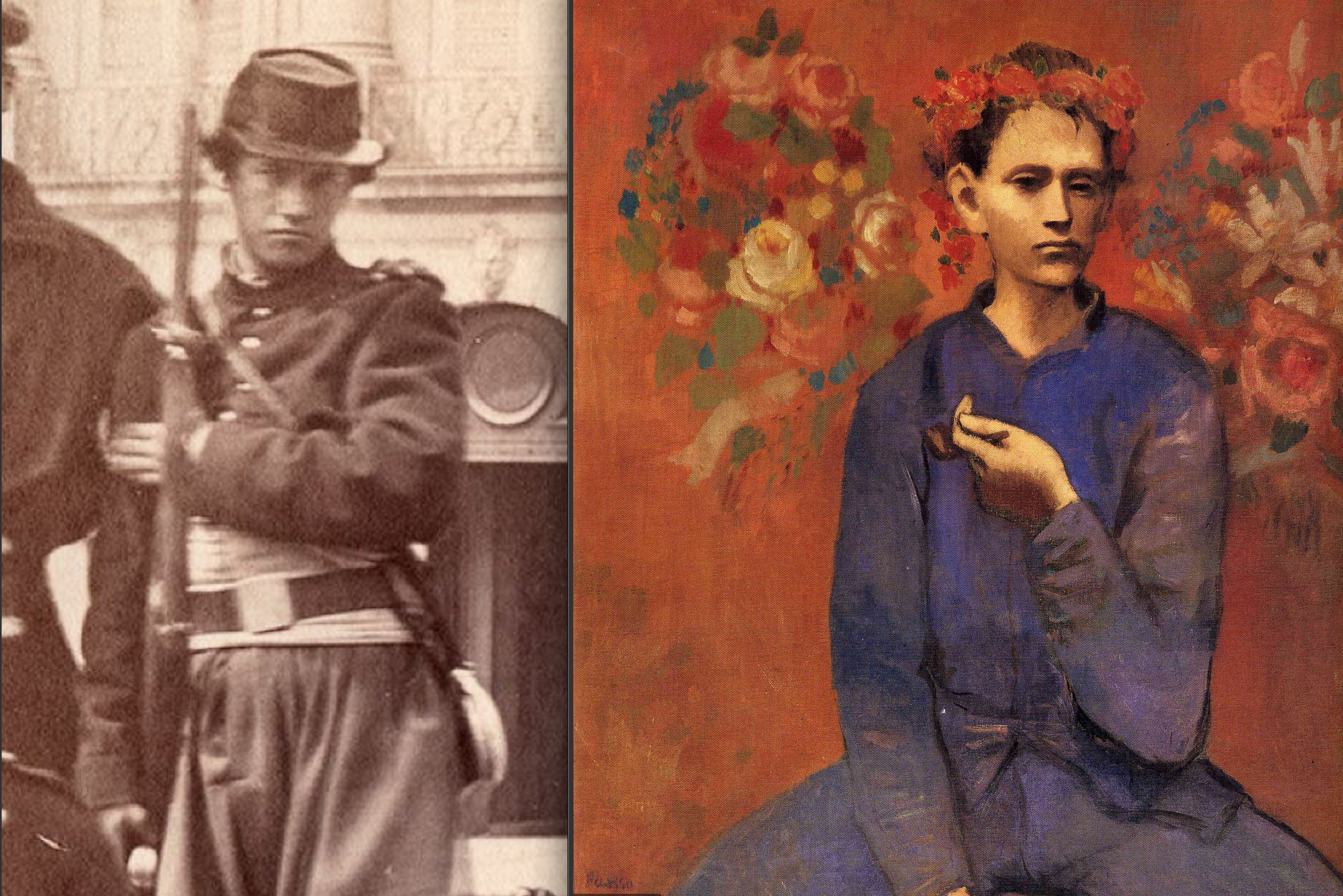

In Bruno Braquehais’ second image Rimbaud stands fifth from the right, adopting exactly the same stance as he takes in the main image: rifle raised, left foot forward. The Mystery Man stands ninth from the right, hooded.

Mystery Man

Can we absolutely pinpoint the identity of anyone in Bruno Braquehais’ main image? So far, definitively, we cannot. (There is no objective proof that Arthur Rimbaud is in these photographs.) But in Braquehais’ second image, where the soldier-boy stands over the fallen Napoleon’s head, we do know the identity of one very special person. This is the ninth figure from the right: the man with the heavy beard and the hood. (He is the only hooded figure in the image.) We can just detect the glint of his spectacles as he peers out towards us from the very back rank, possibly a shy and myopic man, a man who keeps himself to himself, unlike the top-hatted gentleman next to him who smiles with great complacency into the camera. This hooded man – who also wears a military kepi underneath his dark hood – is the celebrated American Beat poet, Allen Ginsberg.

(Just a split-second of bufoonery, testing to see if I’ve put any readers to sleep.)

Ninth from the right – and fourth from Rimbaud – stands the great French realist painter, Courbet. Gustave Courbet was the original driving-force behind the project to dismantle the Vendome Column. In the summer of 1870, during the Franco-Prussian war, Courbet had written a letter to the then-government stating:

In as much as the Vendôme Column is a monument devoid of all artistic value, tending to perpetuate by its expression the ideas of war and conquest of the past imperial dynasty, which are reproved by a republican nation’s sentiment, citizen Courbet expresses the wish that the National Defense government will authorize him to disassemble this column.

The artist went on to elaborate his view that the Rues de la Paix – which actually commences in the Place Vendome – was being degraded by the presence of Napoleon perched on top of his egomaniacal column. When the Communards took charge of Paris the bold idea of cleansing the Street of Peace suddenly made a lot of sense to many people. And on the 16th of May 1871 the maypole of Imperium came crashing down onto a bed of sand prepared for its landing. Its magnificent serpentine coating of bronze – made out of melted-down enemy cannon from Austerlitz – lay in a thousand twisted fragments in the dust. Courbet’s bright idea had run away with itself.

In fact the clandestine, hooded outfit of the painter suggests that he was already terrified of possible repercussions. And indeed, once the Commune had been annihilated by the ‘legitimate’ government of France, Courbet rapidly had to go into hiding. The luckless painter was soon caught however (the new government actually used Braquehais’ photographs to identify many Communards). Courbet was jailed for six months, an extremely light sentence considering his role in the demolishment. (In prison he was allowed easel and paints, but no models.) But even when the sentence had been served this wasn’t the end of the affair by any means. The restored government quickly decided that the Emperor Napoleon’s erectile dysfunction was an huge embarrasment to all self-respecting Frenchmen. (As the column crashes down we can imagine the crowds chanting ‘Not tonight, Josephine!’) And shortly after poor Courbet’s release from prison he was presented with a vast bill for the re-erection. Relatively penniless the painter fled to Switzerland where he died the day before the bill fell due.

So much for the fall of the Vendome Column. But what truly interests about Gustave Courbet is that the painter was a close and lifelong friend of Charles Baudelaire, who for Arthur Rimbaud was the modern poetry-god. (Courbet’s famous 1847 portait of Baudelaire is warm and intimate. The poet sits at a little table smoking his pipe and deeply absorbed in a book. A large white quill stands ready for the page.) Thus a strong literary linkage can be established which makes Rimbaud’s presence in our image much more understandable. As a member of Charles Baudelaire’s inner circle and a lover of poetry himself Courbet might very well have got wind of a young Communard who happened also to be a poet of prodigious virtuosity. And as a painter – supposing Courbet actually met Rimbaud – he would have been very sensitive to his extraordinary beauty. Immediately the artist (who we can safely assume to have known the celebrated photographer, Braquehais) would have recognised in the young man – this Arthur Rimbaud – the perfect figurehead for a historical moment. (Of course an advantage was there for the painter as well. With the handsome boy-soldier as the focus of the composition, Gustave Courbet could then retire to the background, cover himself up as much as possible and remain visually dissociated from the scene in case of later political complications.)

Can we possibly identify the man standing next to Rimbaud?

The Gentle Giant

I’d now like to return to the main image and look at a second figure of significance. This is the towering man who stands next to Rimbaud, who seems a few years older than the poet, who shelters and almost protects him as his left shoulder cordially overlaps the poet’s right. His enormous chest is twice the size of Rimbaud’s. We notice that his gently smiling expression creates a perfect counterpoising geniality which contrasts starkly with Rimbaud’s infernal scowl. Another point to notice is that though this man is clearly a soldier he’s not in full uniform, he’s dressed in army fatigues. Off-duty, he seems faintly amused by his friend’s central role in the proceedings, the soldier-boy’s prominent placement at the heart of the drama. A big, warm sun-like face is the avuncular antithesis of Rimbaud’s dark lunar visage. Together they form an alchemical dyad, opposites conjoined from archetypical extremes.

I assert that we know the identity of this gentle giant. Charles Nicholl, in his Somebody Else: Rimbaud in Africa tells us

Rimbaud was befriended by a soldier in the 88th Infantry, of whom he afterwards spoke ‘with a tender sadness, thinking it certain that he was shot during the Versaillais victory.’

This crucial information comes through Delahaye, the closest friend of Rimbaud’s early years. Pursuing Delahaye’s revelation we discover that the 88th Infantry Regiment were specially venerated during the Commune since they refused to open fire on women and children at a vital phase of the ‘Paris-as-free-state’ experiment when the Versaillais tried to impound Communard cannons. Effectively the 88th Infantry disobeyed orders and prevented a bloody massacre of defenceless civilians during the so-called ‘Louise Revolution’ (when women-Communards in Montmartre became involved in street-fighting).

Delahaye recounts Rimbaud’s belief that his great friend was shot at some point in Bloody Week when the Versaillais regained control of Paris. (Estimates of the numbers shot in Semaine Sanglante vary, some suggest the mass-execution of as many as 20,000 Communards.) The gentle giant standing next to Rimbaud in the Place Vendome could very possibly be this nameless friend. There seems to be a significant closeness between them. (The Californian poet Arturo Mantecon has pointed out to me recently that the giant’s left hand actually rests on the poet’s left shoulder. What I had subconsiously dismissed as an epaulet turns out to be demonstrative and moving evidence of friendship.) If we are correct in this identification we owe this gentle giant a great deal. Without his protection and real friendship Rimbaud could have been murdered in the Rue d’Babylone. And without this champion and protector the poet might never have returned to Paris after fleeing to his hometown in anguish in early May, traumatised by his experience in the Caserne d’Babylone. The certainty that he had one true friend in the city might just have tipped the balance. I feel we can definitely assume that without this friend by his side Arthur Rimbaud would never have taken his central place in the Braquehais portrait.

Yet the gentle giant – this hero who saves the lives of women and children in Montmartre and who then saves Rimbaud in the Caserne d’Babylone, – stands in the shadow of a tragic destiny even while he smiles and lays his hand on the shoulder of his magnetic young friend. When death pits are dug in parks and squares, when thousands of Communards are marched in chains to mass-graves, our gentle giant sadly loses his life. Delahaye is clear: Rimbaud believed his only friend was murdered in the Semaine Sanglante.

We may need to thank this man for one more thing. It is possible that our unknown soldier of the 88th regiment actually warned his young friend that after the excitement of the Place Vendome photoshoot his face would be ‘on file’. He’d be a marked man!(As I pointed out earlier, the Braquehais images were actually used to track down Communards.) Perhaps Rimbaud’s champion, with his greater knowledge of the world, instructed the poet to get out of Paris just before the commencement of Bloody Week, a few days after Braquehais’ photographic happening.

Ironically, the gentle giant may himself have been condemned by the act of standing next to Rimbaud in the bright May sunshine. Perhaps the poet was so certain of his friend’s death because he understood that the flattering lens actually represented the barrel of a gun. (Parisians complained during the Commune that wherever they went they were confronted not only by armed insurrectionaries but also by those they termed ‘collodion-gunners’.) Now we realize that the unknown soldier may have saved Rimbaud’s life twice in the space of a month.

Child-Pantocrator

A banal countryside somewhere in the wilderness of Rocks. The midday sun is a machine of death countersinking light into the brain. (The riveting of all things has come loose.) Hot screws penetrate the cortex, winding into bone.

Alas, the Gospel has gone by. The Gospel. The Gospel.

In the heatwave someone is suffering from sunstroke. He’s been immobilized in the house, a dehydrated fieldworker probably. His memory seems to be affected, he’s forgotten his own name. They’ve brought him indoors, given him the day off, bathed his temples with cool well-water. He’s resting in an airless attic, isolated.

He’s less than nineteen, still a boy really.

Up in the dusty rafters pigeons hum. Muted wingbeats fan a superheated mind.

Drink.

When he whispers he is taking flight into the past, hidden from him like the doves in the roof: his secrets fight with one another in the darkness. Once there were innocent flights of wanderlust, bids for freedom, bohemian roads. Once there were out-of-the-body trajectories across transdimensional bridges of light. But he travelled too far into the sun and crashed to the shadows of the Rue d’Babylone. Then the wax which had sealed his wings melted as hot blood pooled behind his knees. Then came the sulphurous fogs of Camden Town.

Through the spirit we go to God. What a disaster!

Now he’s reached the lowest point. With the stigmatic wound where Verlaine nailed him throbbing like the pulse of Jormungandr, he’s finished. With his left arm in a sling he sits and writes. In between dizzying panic-attacks he pulls himself upright at a packing-case desk and describes a Faustian pact with occult principalities. (Now will-to-power intersects with hell-on-earth.) In the pages of a strange discontinuous diary he confesses a long history of possession. Certainly he’s been given the miraculous gifts and shown the super-utopian visions. Yes! He has even levitated like Simon Magus, using his breath to manipulate weightlessness. But the siddhi have brought only overshadowing. (The two-faced spirits have often told half-truths in order to finally insinuate the lie.)

They promised me to bury in the dark the tree of good and evil, to destroy the dictatorial honesties, so that I might bring forward my very pure love.

If evil is only a catalyst there is no danger. With our energies behind you you will push against evil and lever yourself towards grace. (All men believe in saints after all. And that selflessness proves something about the world.) If you overwhelm yourself with our powers we’ll show you where the rites of the Great Work end. You’ll change the world with a cabbalistic alphabet. We’ve shown you the sunchild dancing in the Tree of Life. You’ve seen the vision of Seth, the third son of Eden. Now imagine your good, its implementation. To a good man all things are good. Remember that!

Yet deep down he knows he’s not good enough. (It was vile to use Verlaine as a stepping-stone. He deserved the bullet, he deserved to die.) Now he feels filthy inside. Christ Jesus! In broad daylight he turns and looks over his shoulder. In the still of the night there are others in his solitude. He has reached the spiritual battleground of near-madness.

Drink! No more dust behind you.

He sweats in the noons of Thermidor. Outside they’re working in the fields. Now rays of sunlight move the harvesters this way and that like little marionettes. (Smells of burning float through a tiny window.) They’re reaping hot coals in the harvest of hell. Now commandments of Shadowmouth reverberate, knife-like and strident, sharp decrees stabbing. The glad time of his harvest will never come.

Be as wise as serpents, as gentle as doves.

Sometimes when he hears the night-train to Luxembourg he returns to Somers Town in the rain. (Winged thoughts stir like a pigeon dreaming in the eaves.) Once upon a time he was close to the place and the formula.

The spiritual battle is as brutal as the battle of men. But the vision of justice belongs to God alone.

Picasso’s pen-and-ink study of Rimbaud.

Recent Comments