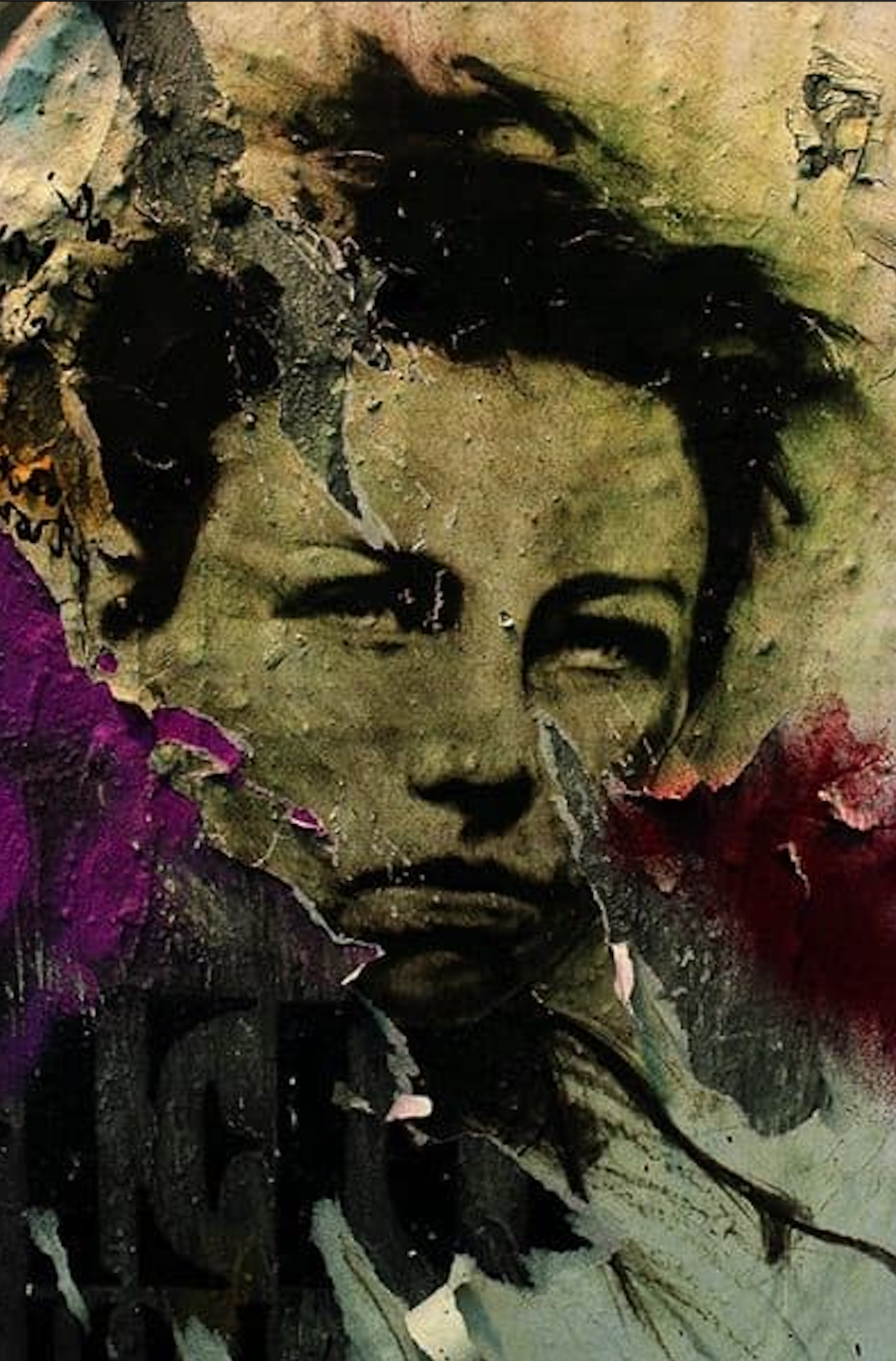

The dark side of Arthur Rimbaud. (A portrait of the poet by Ernest Pignon-Ernest, 1978, drawing on the Etienne Carjat studio portrait of October 1871.)

Rimbaud on File

I saw myself in front of an infuriated mob, facing the firing-squad. (A Season in Hell.)

There is a famous sentence in a French police dossier of 1873: ‘Young Raimbault (sic) belonged, under the Commune, to the Paris Irregulars.’ There is nothing tentative about this statement, the file is clear: ‘young’ Rimbaud is accused of a crime against the state. In 1873 any definite affiliation with the Communard regime was still an imprisonable offence. To have actually been enlisted in the Paris Irregulars in 1871 was much more dangerous. During Bloody Week it had meant the firing-squad.

At the time when this file on him was compiled Rimbaud had fled to London. In 1873 many of his fellow-communards were also London-based, hardcore revolutionaries like Andrieu and Vermersch. Rimbaud (and Verlaine) fraternised and socialized in these circles. They most probably rubbed shoulders on several occasions with Karl Marx who quite frequently lectured French Communards in London.

Do we know how the secret intelligence on ‘young Raimbault’ was gathered? Was it based on anything more than hearsay? Was there ever any substratum of proof for such an explicit and clinical assertion? An interesting fact has come to light regarding the photographer of the Place Vendome, Bruno Braquehais, evidence which may possibly help to elucidate these questions.

Bruno Braquehais, pioneering photojournalist of the Place Vendome.

An Objective Artform

Bruno Braquehais was born in Dieppe in 1823. Deaf from birth he was educated at the Royal Institute of the Deaf and Mute in Paris. In his twenties Braquehais started working for a well-established Parisian photographer who specialized in coloured daguerrotypes and stereoscopic prints. At some point he married his employer’s daughter and eventually inherited his father-in-law’s business. Throughout the 1850’s and 1860’s Bruno Braquehais continued to explore portraiture. His subjects were usually fashionable artists, minor composers and ballet choreographers and the like. Relatively successful in this field he also created nude studies (which were coloured by his wife, Laure).

Bruno Braquehais was 48 when the Commune was declared in 1871. By now he was quite well-known and had exhibited his portraits at several notable Parisian institutes and galleries. However with the rapid evolution of the Paris Commune Braquehais suddenly transformed his modus operandi. Overnight the studio photographer became a photojournalist, one of a new breed of objective artists recording historical events with advanced technology. Bruno Braquehais became one of the mysterious ‘collodion-gunners’ who terrrifed the citizens of Paris with their ‘painting-machines’. Parisians who’d lived through the Prussian seige were not easily intimidated; they were accustomed to the sight of armed Communards on street-corners. Yet when bizarre spider-like contraptions started appearing on the shell-scarred boulevards, Parisian workers – most of whom had never been inside a photographic studio – were baffled and frightened. Strange three-legged monsters had invaded their city! Black boxes raised on stilts remained threateningly pointed in their direction for hours at a time, while trousers moved about disconnectedly beneath huge sombre skirts. (It took a long time to shoot a collodion plate. It was dangerous too; cameras could explode with a build-up of nitrate.) Civilians spread the half-serious rumour that these black boxes were some new secret weapon resourced by the Communards to perpetuate socialism. And in a sense they were right because images captured by Braquehais (among others) did eternalize the demographic experiment which turned the world upside-down for seven weeks.

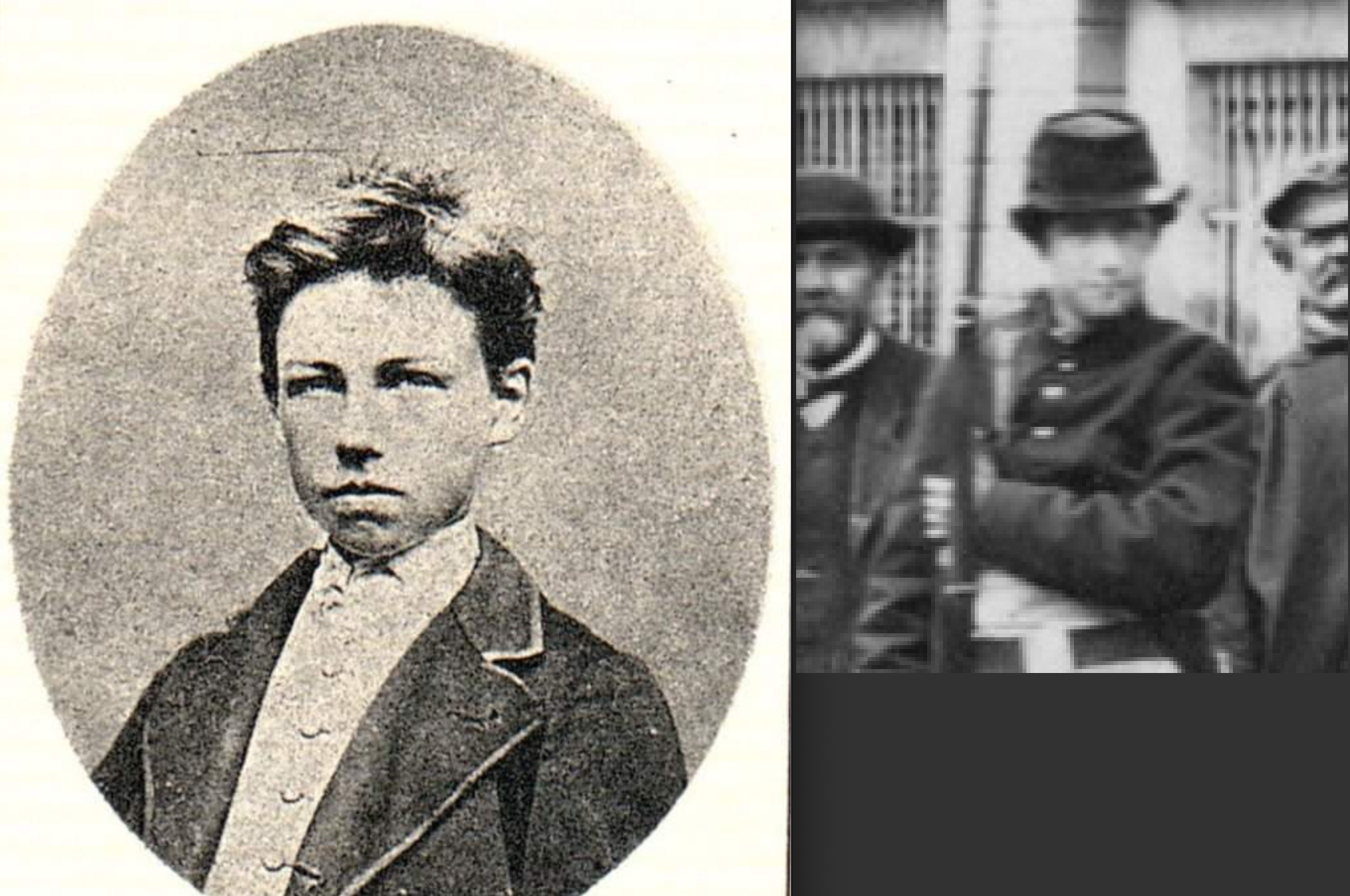

Braquehais shot a great number of Parisian scenes during the Commune, perhaps as many as 200. In these he portrayed insurgents of both sexes at the barricades, showed mixed classes in carefree mood in the streets, captured collapsed railway-bridges, picturesquely ruined buildings and so on. From a total of approximately 200 images he published 109 in a pamphlet titled Paris During the Commune. (The unpublished images have all been lost.) It is important to emphasize that the published Braquehais photographs were largely forgotten until 1971, which partly explains why Rimbaud’s presence in two of them was never detected before now. It is also important to note that among Braquehais’ 109 plates in Paris During the Commune the standout image is the Place Vendome. The picture which seems to present us with a new portrait of Arthur Rimbaud is the master-image of the entire collection.

While we are discussing Braquehais I cannot resist suggesting that a very wonderful phrase of Rimbaud’s – which has delighted and puzzled many commentators – could be related to the technical process of producing a collodion wet-plate.

I dried myself in a criminal air. (A Season in Hell)

Braquehais would have had to bring a portable dark-room to the Place Vendome because the entire procedure of coating a glass plate with collodion solution, exposing and developing the image all had to be done within the space of ten to fifteen minutes. The crucial ‘drying’ of the plate would have been done in situ, and Rimbaud, with his interest in the new ‘objective’ artform might well have been the witness of his own theophany as a negative image magically emerged. It would be in keeping with Rimbaud’s techniques to superimpose a straightforward physical phenomenon on top of an abstract reality in order to achieve the strangeness of this phrase, which works so well because criminals must harden themselves, ‘bake’ the outer crusts of personality, evaporate all softer elements.

Bruno Braquehais’ master-image from Paris During the Commune. Rimbaud stands on the plinth at Napoleon’s feet.

House-to-House Searches

The long-forgotten photographs of Braquehais are now universally admired. What is often not remembered about Paris During the Commune is the fact that this pamphlet was used by the French secret police as a reference manual for hunting down underground Communards. Agents would actually take copies of the Braquehais publication with them as they seached house-to-house for fugitives, identifying suspects by checking them against Braquehais plates. (Suddenly the humorous term ‘collodion-gunner’ acquires a more sinister resonance.) Effectively Bruno Braquehais, against his will, was transformed into a forensic photographer. His work was resourced as incriminating documentation, undoubtedly causing the artist much heart-searching and hand-wringing in the process. Bruno Braquehais understood that during Semaine Sanglante – the bloodiest week in French history – numerous men and women were executed as a direct corollary of the click of his lens-shutter.

Fire! Fire at me! (A Season in Hell.)

Now we can perhaps more fully understand that Rimbaud’s moment of bravado and machismo in the Place Vendome may have powerfully fed into into his lifelong paranoia. To explain the poet’s fuming and fretting from the African continent biographers have come close to assuming something like a persecution complex on Rimbaud’s part. He grills his mother from Abyssinia, he involves his family in complex liasons with French military authorities over questions of his eligibility for National Service, and all this while he knows very well that he is exempt because his older brother Frederic has already served. Then there is the mysterious and unsavoury business of this same brother’s attempt to blackmail the poet, apparently hoping to raise the money for his marriage. (Frederic was a bus driver and, we assume, badly paid. And he guessed his younger brother had amassed a small fortune in Abyssinia.) What exactly was the dark secret that the apparently not-so-brainless Frederic threatened to expose? Frustratingly we don’t know much about any of these issues. Most of the letters from the family side have been lost so we only hear Rimbaud’s part of the dialogue: an everlasting lamentation on the emptiness of his life mingled with hysterical outbursts regarding military authorities. I don’t think it at all unlikely that the Place Vendome portrait – considered by the French police to be the scientific record of a crime scene – could have haunted Rimbaud for the rest of his short life, casting a long and persistent shadow in his mind. As we have already seen, the demolition of the Emperor’s ‘sacred’ column was by far the most provocative statement made during the Commune.

What sacred image are we attacking? (A Season in Hell.)

Marching to an Open Grave

Rimbaud must have known that Braquehais’ pamphlet was being used to identify ‘terrorists’. Furthermore, knowing that his friend from the 88th regiment – the man I have previously called the Gentle Giant – was shot during Bloody Week, Rimbaud may well have traced a connection between his friend’s tragic fate and the infamous Braquehais image of the Place Vendome. He may have reflected ruefully that his friend guaranteed his own death by standing beside him so protectively on the plinth. One thing is clear. Had ‘young Raimbault’ remained in Paris during Semaine Sanglante he too could have been marched in chains to a grave-pit and summarily executed without trial. (Some estimates of Communard dead reach the terrifying figure of 20,000.) The poet’s life of relentless wandering, and even his desire to put a literary lifestyle behind him, make more sense if we know, as Rimbaud may have known, that the evidence against him was scientific, forensic and unambiguous.

I called to my executioners to let me bite the ends of their guns, as I died. (A Season in Hell.)

In my next piece I am planning to discuss the problematic timings of Rimbaud’s movements in April and May of 1871. Is it feasible for him to be in the Place Vendome?

Please stay tuned!

The triumvirate of the Place Vendome.

Absolutely fascinating. Keep it going. Please.

Thank you sincerely, Richard Livermore. There’s a new piece on the way, looking into the identity of the Third Man. Plz stay tuned and spread the word.

Wonderful piece, Aidan. I can see a book in this!

Here’s the funny thing, Glenn. I was halfway through writing a novel about Rimbaud when this revelation happened. Now the novel lies abandoned and I seem to spend my waking and dreaming life in the Place Vendome. Thank you for your encouragement, slowly, slowly.

Brian Hinton, poet and curator, biographer of Joni Mitchell and Van Morrison has asked me (in an email) to post the following here. I am indebted – and delighted! – to have his too-kind acknowledgments.

‘Some very fine scholars can account for Rimbaud’s every day, laundry lists, choice of breakfast et al, but it takes a great poet to understand him in spirit.’

‘And Aidan Andrew Dun joins the line from Davide Gascoyne right up to Bob Dylan and Patti Smith, all writers and musicians who channel his essence and make it relevant to a new age. ‘

Dr Brian Hinton

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Hinton

Hear, hear!

Harry Simmons, sincerely, thank you! So encouraging.

New post tomorrow.

Rimbaud forever!

Reference for the 1873 Secret Police Dossier?

Robb, Steinmetz and Nicholl all refer to this if I’m not mistaken. An ankle injury stops me getting to my library at the moment but I’ll certainly look into references for you when I can.