Withnail and I: Psychotropic Cinema

Eternal refugees: Donald Twain and his understudy

The Gotterdammerung of Hippiedom

Acclaim can sometimes turn into condemnation.

To illustrate: young Damian – cinematographer friend – fell head-over-heels in love with Withnail and I, the British cult-movie portraying the Gotterdammerung of hippiedom. Having decided to screen it on the side of his house he invited all his friends to the opening-night of his pleasure-dome, the inauguration of his starlight cinema. Yet the summer evening’s ‘entertainment’ actually commenced a little earlier with an invocation to deities of visualization and hallucination. Before turning the projector on – and in the spirit of the film itself – my friend handed round a large tureen of freshly-brewed psychotropic mushrooms. Everyone knowingly dipped a cup or two. And after a while, in the dusk, the film began.

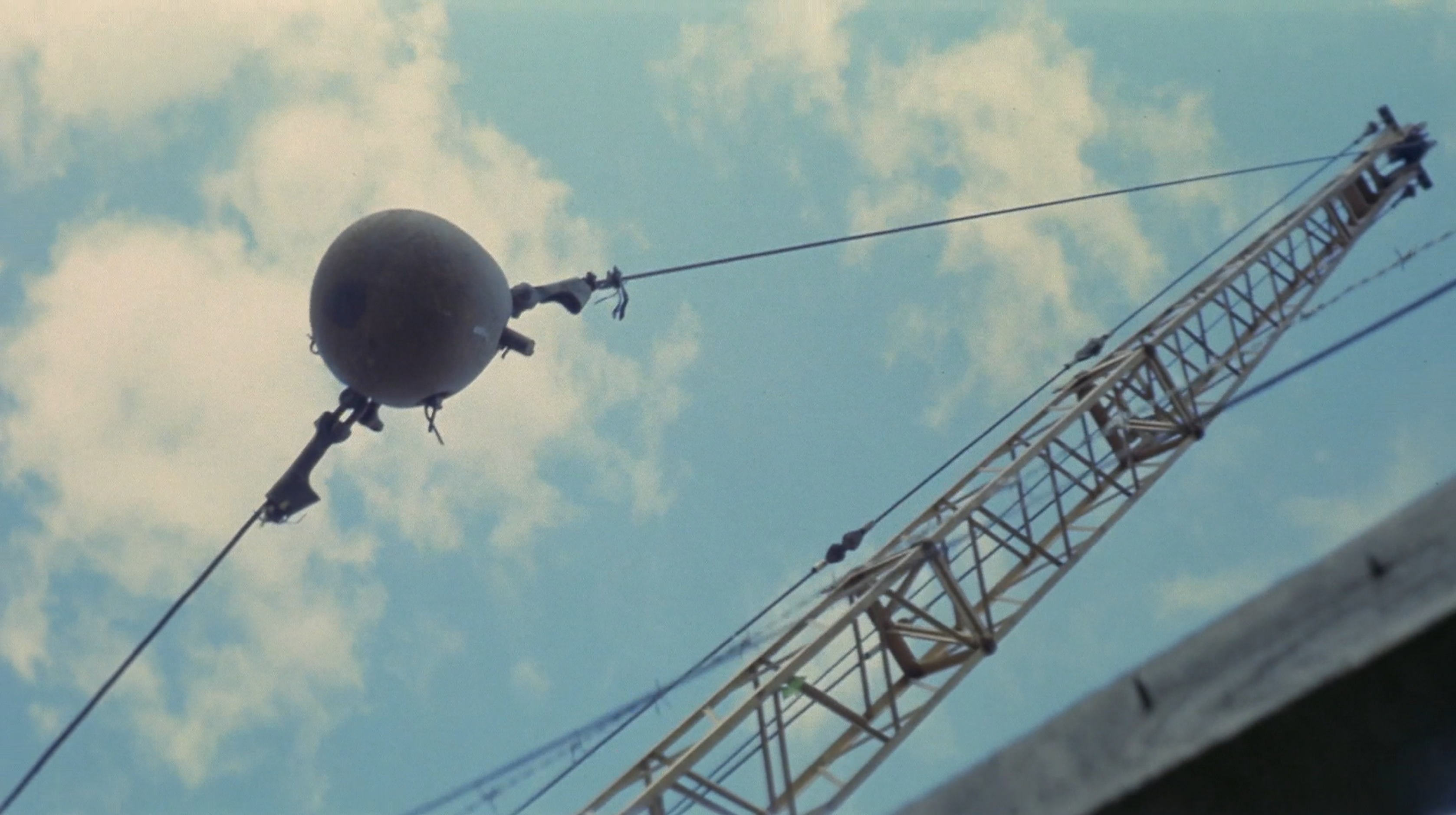

The destruction of Georgian Camden as film-set for the shooting of Spengler’s Decline of the West

The Wrecking-Ball

Quite early on Withnail and I presents one of the most powerful cinematic sequences of all time. For sheer thunderous energy it compares with the famous helicopter assault in Apocalypse Now. There the machine-assisted rape of a coastal Viet Cong village is reinforced by Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries. In Withnail the scene is only the demolition of some Georgian terraces in shabby 1960’s Camden Town but – with a Hendrix soundtrack absolutely dwarfing Wagner’s best efforts – an image of merely local obliteration somehow becomes the final destruction of all cities. With the words ‘Free to those who can afford it, very expensive to those who can’t’ we cut from the neurotic coziness of Uncle Monty’s drawing-room to the wrecking-ball against the film’s only blue sky. Now as the terrifying Hendrix rendition of All Along The Watchtower crashes and surges we seem to witness the collapse of the western world. The wrecking-ball hangs like a hydrogen bomb in the sky. Syncopated slashings of stratocaster power-chords line-up with the annihilation of the metropolis (which is also Blake’s prison ‘built with the stones of the law’). And suddenly – miraculously – the prisoners, two out-of-work actors stranded in the underbelly of London, are set free . . .

Thus Withnail gathers steam and prepares us for the horrors of Uncle Monty’s cottage in the rain.

At exactly this point in my young friend’s summertime screening cinematic hypnosis and expanding consciousness got out of hand. Just as the wrecking-ball crashed into the terrace and Jimi signalled the end of the world – just as the celebrated ‘wind began to howl’ – the entire audience rose to their feet as one man and began hurling chairs and tables at the side of the house. Bombarding the open-air ‘screen’ with a barrage of garden-furniture each guest became an individual demolitionist tearing down the urban fabric of Babylon. Under the influence of Damian’s magic potion a psychological superorganism launched its own tribute to the film in the form of a broadside of deck-chairs and sun-loungers.

Acclaim was being expressed as destruction.

‘There are gonna be a lot of refugees.’

An Experiment in Decadence

Released in 1987 Withnail rapidly sank out of sight, a resounding flop in spite of some positive reviews (though the PC brigade claimed the film was homophobic, absolutely untrue because Uncle Monty – apparently based on Franco Zeferelli – is carefully presented not as a caricature but as a complex and rather wonderful man whose loneliness happens to have spiralled out of control, someone who nurtures in himself both innate decency and a romantic imagination). Withnail was crucified at the box-office, evaluated as an eccentric farce. But then with the advent of the VHS format an underground reputation spread by word-of-mouth and the establishment couldn’t stifle the work any longer.

As if commenting on its own supresssion – and resurrection – the theme of magnificent failure resonates within the film. Yet this failure is much larger than the failure of Withnail himself, a blue-blood actor who feels entitled to stardom, but whose internal saboteur works overtime to undermine his narcissistic ambition. In the conceptual background of the film is the relationship of Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine, a relationship which famously imploded in Camden Town (in 1873). The project of these two quintessential French poets was an experiment in decadence conducted in an atmosphere of narcosis set against a backdrop of destitution. (With Rimbaud wanderlust bordered on vagabondage.) Inevitably – just as in Withnail – this brave enterprise went to hell. Rimbaud, who stopped writing at eighteen or nineteen, represents modern literature’s most poignant foundering, a Mighty Youth condemned to an early death. Yet – like Withnail himself, another rejected candidate for recognition – Rimbaud has enjoyed unparalleled posthumous fame, to such an extent that he’s often quoted in hiphop, where he’s seen almost as some kind of messianic figure. (Verlaine – rather like the ‘I’ of Marwood – is more obscure today, an important lyric poet perhaps but certainly no streetwise prophet.)

I’m going to be a star

Don Quixote for the Psychedelic Era

Withnail and I can also be read as Don Quixote remodelled for the psychedelic era. (The formula is timeless: a visionary overlord has to rely on a worldly-wise retainer.) The film is often simplistically described as a comedy, but just as with Cervantes’ masterpiece it actually occupies a rarefied zone somewhere between comedy and tragedy. (It is also acutely-observed social commentary with no egregious sense of taking sides.) Inimitably played by Richard E Grant, Withnail himself is a horrifying synthesis of spleen and finesse, psychosis and panache, bitterness and wit, while the ‘I’ of Marwood (never named in the film) is his relatively lacklustre sidekick (played by Paul McGann). Marwood’s courageous pragmatism is the constant foil to Withnail’s fluorescent paranoia. Yet the former’s loyalty is tested to the limits in the course of the drama, which will end (without giving anything away) with both characters defined by the dramatic role each seems destined to execute. Marwood is perfect for some realist part in the countryside of quiet stagnation which is Chekov: he’s essentially an accessible bourgeois actor. Withnail, on the other hand, is born for epic roles. He’s astrologically – almost – cut-out for tragedy. He’s a natural fountainhead of hyperbole and metaphysics. There are millions of Marwoods. There’s only one Withnail.

Thank God!

Where Grant’s character is concerned – by design – there are problems. His ‘casting’ is not straightforward and inevitable (as it is with Marwood, who we see normalised, cleaned-up and sanitized by the end of the film). No, Withnail has the tragic flaw which necessarily stigmatizes greatness. Richard E Grant’s dramatis personae is a bitch. He’s as twisted as Hamlet himself, a coward in spite of lyrical blusterings, a class-traitor in relation to his friend, an unemployable genius whose madness overboils. And in the film’s searing finale – with caged wolves symbolizing housebroken wildness and ‘civilized’ insanity – Withnail delivers Hamlet’s ‘sterile promontory’ monologue which builds to the acerbic:

‘What a piece of work is a man.’

Here, Grant gives us the Elizabethan golden age in the understated drawl of Marlon Brando. This heartbreaking coda to the movie demonstrates that if Bruce Robinson – director of Withnail – had been given the resources to cast Richard E Grant as ‘the Dane’ we would have been given an utterly contemporary and ‘marvellous’ Hamlet for our times. (Of course there exists the 1969 film-version of Hamlet in which the lead is played by Nicholl Williamson, and Ophelia by Marianne Faithful, one of the best cinematic Shakespeares ever achieved. Here we get a taste of what Grant could have delivered had he been let loose in the most demanding of all classic roles.)

Caged in compulsion with the wolves

Negative Capability

Withnail tightropes a fine line.

In the Mother Black Cap public-house sequence quite early-on in the film, McGann – regaled with petunia oil – is called ‘perfumed ponce’ by an angry thickset Irishman who (judging by the grafitti outside the pub) is very possibly an IRA member, most unsympathetic. Withnail, trying to fend off this queer-bashing Provo, first claims to have ‘a bad heart.’ (Double entendre: he can love no-one but himself.)

‘If you hit me it will be murder.’

When this fails to deter the assailant he whines:

‘My wife is having a baby.’

As Grant offers these words his demented blue eyes – red-rimmed and sleep-deprived – fill with tears. He hardly gets his line out, it’s mumbled under his breath. A brazen lie sticks in his throat and we laugh at the sublime buffoon. (We all think the same way, it’s human nature: Keep the jokes coming, look out for the clowns.) Yet there is a secret key to this sequence. The tragic fact is that, during rehearsals for Withnail, Grant’s wife lost their first child, and this loss, mirrored in the actor’s eyes, helps him to deliver one of the funniest lines in all cinema. Here is Keatsian ‘negative capability’: the dual action of two opposite forces working together to actualize synthesis beyond the categories: the formula of genius.

‘We can never get over grief but we can get around . . .’ (Richard E. Grant.)

Taking the ‘fresh air’ in Regent’s Park

Counterculture Pirates

Some connoisseurs of the film feel that Richard Griffiths (1947-2013) is the real star of Withnail and admittedly his performance as Uncle Monty is a tour-de-force. A bumbling cyclops threatening intercourse per anum never exuded such conviviality. From his class-vantage Uncle Monty views the poor, cornered Marwood as little more than a curly-headed rent-boy. And yet his predatory visit to the cottage in the dead of night has been catalysed by the treacherous Withnail who has told his uncle that his friend is a ‘toilet-trader’. (This betrayal is the price of admission to the social ranks who take weekend-breaks dans la nature.) We can just imagine Richard Griffiths drooling Verlaine over his crumpets: ‘O, my boys, my boys, we inhabit un paysage choisi, this promised land, this England, mother of trees!

Another great engine of Withnail often goes unsung. A character and a personality in its own right this is the machine which propels the road-trip aspect of the film: a six-cylinder one-eyed Jaguar XK, a 3.8 litre shamanic vehicle of liberation. Steering for action in the rain-curtained Lake District this gun-metal grey battlecruiser of a car sails our counterculture pirates down waterlogged motorways of fate, Marwood in his tip-down dark glasses, Withnail in the death-seat, way-too-cool for shades. It’s this low-slung Jag with its single windscreen wiper which powers the adventure of outsiderhood which is Withnail. The car seems totemic, a camper-van wouldn’t have served. This sleek but damaged pirate-ship is the physical badge of the film’s ‘spiritual nobility’: the vessel of a true rite-of-passage.

Withnail and I is psychotropic cinema, to be screened forever in a pleasuredome of ice. Or failing that, an open-air summertime picture-palace (with no seating-arrangements this time around, with guests encouraged to adopt lotus-postures on the lawn.)

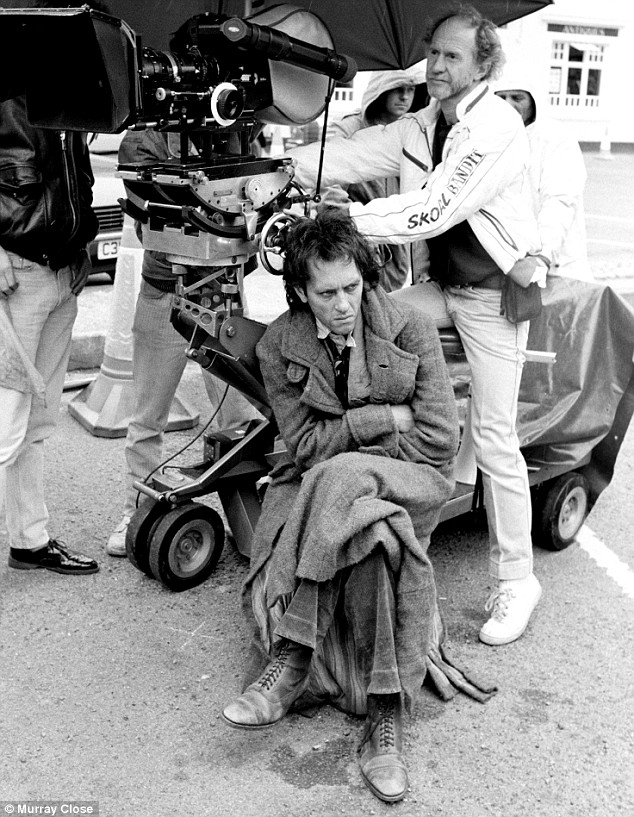

Grant incubating venom in a spare moment on-set

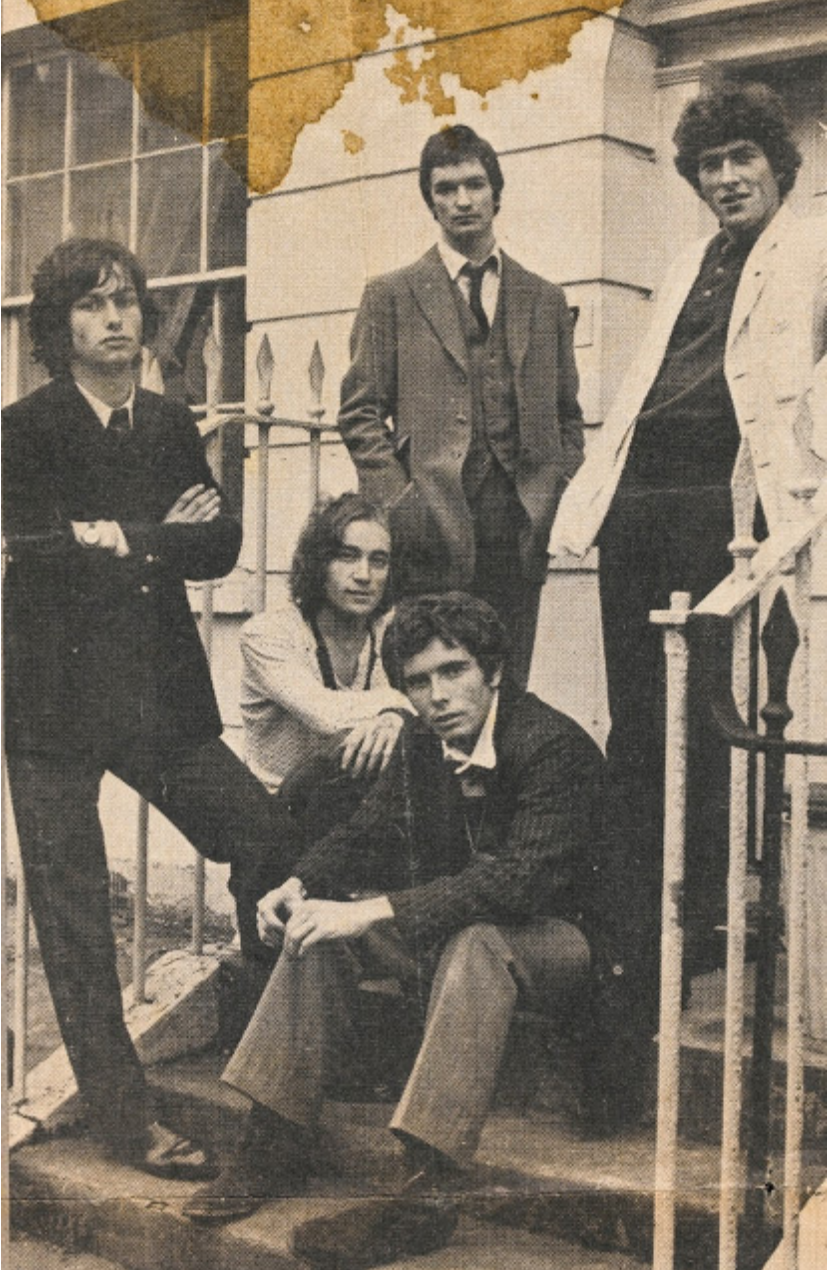

The original bad-boys on the doorstep in Albert Street, Camden Town. Robinson is extreme left and Viv MacKerrel – inspiration for the character of Withnail – is centre back.

McGann and Grant know the chemistry is working

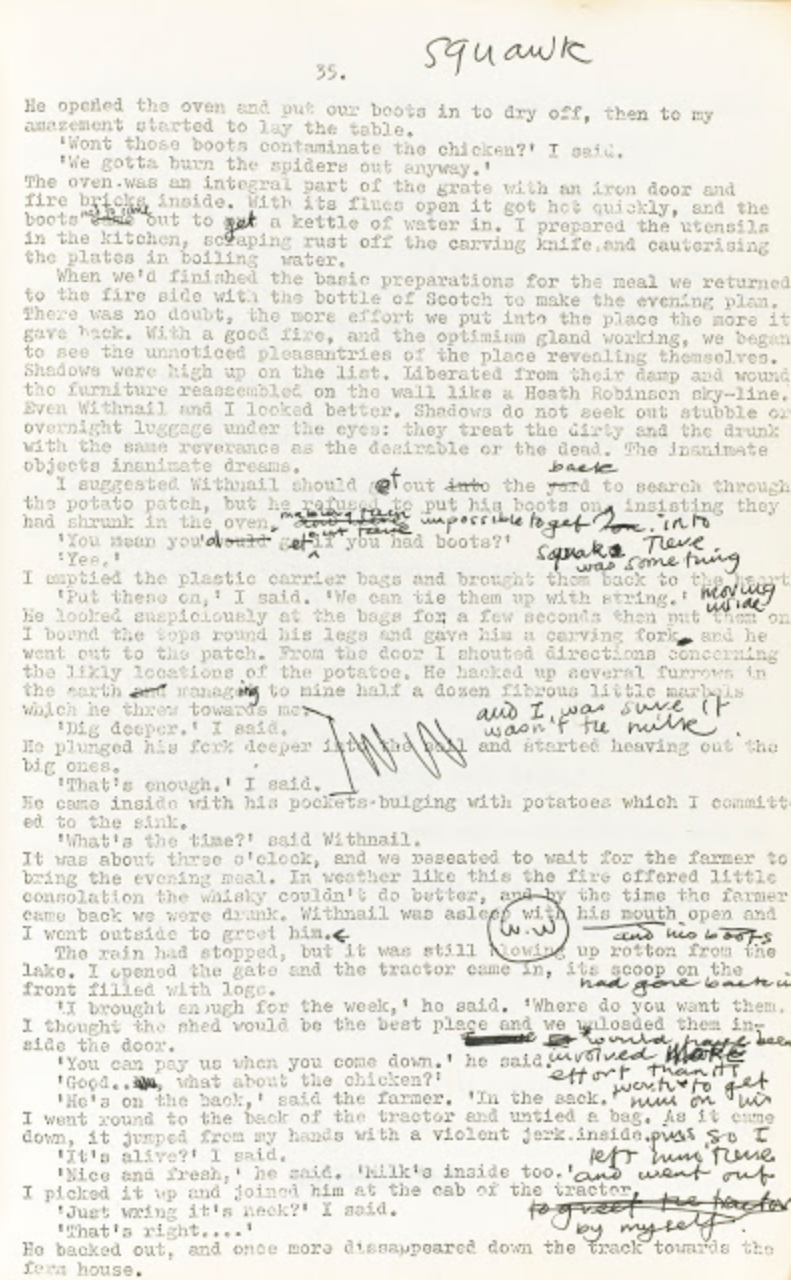

A page from Robinson’s original novella which was never published but reworked as the legendary film-script

We’ve come on holiday by mistake

Recent Comments